Australian photography had a massive presence at the 19th Pingyao International Photo Festival (PIP) in China, with six shows curated by Australians including two of the 10 Featured Exhibitions.

PIP is one of the biggest and most prestigious photo festivals in the world, staged across the ancient city’s abandoned factories and religious temples from September 19 to 25. We’re talking hundreds of exhibitions with work from thousands of photographers, a festival program booklet with over 200 pages, and a crowd of god-knows-how-many attendees.

While it’s reasonable to expect Australian photography to have some presence at PIP, it actually has built a significant platform, partly thanks to Australian photographers and curators regularly contributing shows over the years.

The Dingo’s Noctuary by Dr Judith Nangala Crispin and Rodents Mort by Jeff Moorfoot appeared as part of the Featured Exhibitions. The two exhibitions are linked not just by the artists’ country of origin, but also due to their prints showing animal carcasses and are made using alternative processes.

Moshe Rosenzveig, founder of Head On Photo Festival and regular Pingyao contributor, went over with the Head On Portrait Prize Finalists and Michael Jalaru Torres’ Native and Scar.

Additionally, Alison Stieven-Taylor curated The Female Eye, which featured works by Australian artists Nicola Dracoulis, Kerry Pryor, Ilana Rose and Helga Salwe; and RMIT had an exhibition called Transitions.

Here’s a taste of what the Pingyao crowd saw:

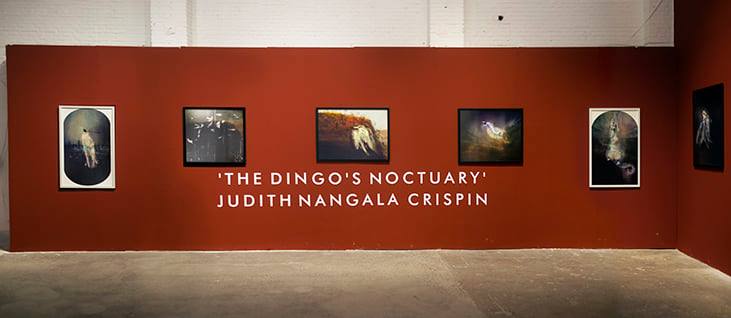

The Dingo’s Noctuary

Canberra-based multi-disciplinary artist, Dr Judith Nangala Crispin, began work on her new project The Dingo’s Noctuary in 2018. While the project will culminate in a book consisting of several art forms, from poetry to photos and drawings, for Pingyao Jeff Moorfoot curated a selection of Judith’s lumachrome glass prints from the series.

The prints show roadkill animals arranged with various other natural materials like sticks, mud, blood, resin, seeds, or leaves. The complex process involves layering the arrangements on perspex over a base layer of light sensitive paper, which is exposed under natural light for between 12 to 36 hours.

Here’s Judith’s project statement from LensCulture:

‘This series was created in response to the death of a close friend – a very old Warlpiri tribeswoman named Lily. During our ten years of friendship she spoke to me often about the sentience of country, and about how all living creatures result from ‘Country thinking things into being’. She insisted people could develop a shared language with the sentient landscape. After her death I wanted to talk to Country, as she so often did. I wanted to tell it I had loved her. So I gathered roadkilled animals and put them on light-sensitive paper with mud, sticks, seeds, grass …the bones and arteries of Country – and I let sunlight create images in very long exposures. This process became more complex as I began to understand how light works – I added several layers of glass separated by spaces, to create textures using distance – shades of light and dark. And I scratched or drew on different pieces of glass.’

‘The thing I have found most surprising, and comforting too, is the gentleness with which light surrounds an object over a very long exposure. You’d have thought a lumen print would yield only a stenciled outline, but with very long exposures on elevated glass, the light gets right underneath the form, sometimes creating unexpected detail. There is something touching in this – as though the light were holding the body in its arms. When people die, Lily used to tell me, they go back to Country, because they are just a part of Country, they always were.’

Lumachrome glass printing is an experimental process which Judith says she invented, drawing inspiration from experiments carried out by the father of photography, Henry Fox Talbot.

‘Some of the perspex layers are used as cliché verre, covered in mud, wax, blood or paint, and scratched with wire to create lines and shapes. The animals and birds are brushed with salt or other agents to ensure the fine detail you can see in the prints. Sometimes I am using contact printing methods. I am also using raw chemicals and acids as well as household chemicals and biochemicals.’

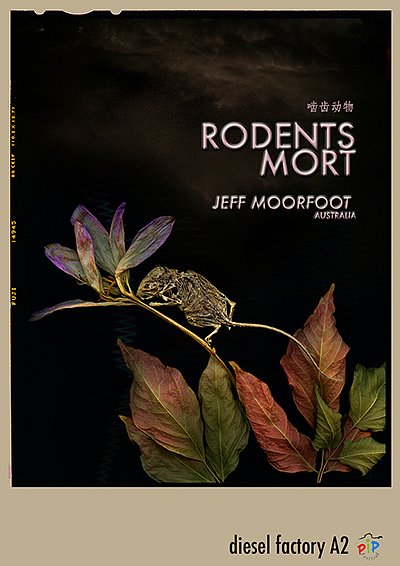

Rodents Mort

Jeff Moorfoot, fine art photographer and Ballarat International Foto Biennale founder, is a regular feature at Pingyao. He’s curated and shown a handful of exhibitions over the years, as well as participating in portfolio reviews and other events.

He’s become a real head-turner among the crowd at Pingyao, a phenomenon that’s likely accentuated by his Grateful-Dead-meets-Santa-Claus appearance, which stands as a polar opposite to the clean cut appearance of the Chinese. He seems to be a very popular subject to photograph.

His show, Rodents Mort, consists of three triptyches – art pieces divided into three prints or sections – made between 2016 and 2018 of rodent skeletons.

The skeletal remains, in various stages of decomposition, are arranged and captured using a flatbed scanner. Rodents Mort appears in Jeff’s first major photo book, Scan, alongside other pictures made mostly using organic matter found within his garden.

‘I love the quality of the light and the rapid fall-off that the scanner produces as well as the shallow depth-of-field and the ability to produce very large files capable of enlargement much greater than I can produce with my A2 printer,’ Jeff writes in the introductory to Scan. ‘I use the computer pretty much the same way as I used a wet darkroom for making prints, with manipulation of images limited to contrast, density and colour control because I want my images to appear photographic even though they have never been near a camera or a roll of film. I now use an A4 Epson V700 flatbed scanner coupled to an iMac desktop and I output archival prints on an Epson 3800 printer.’

While Jeff is semi-retired, he’s keeping himself busy. According to his Facebook he’s back over in China to hang another show, Antipodean Mnemonic, at the 2nd Baohe International Photo Festival in Hefei.

Native

For the last few years Moshe Rosenzveig has toured the always-excellent Head On Photo Prize Finalist exhibitions on the international photo festival circuit, including to Pingyao.

This year there was an opportunity to take another show along, and it was a no-brainer to take a Head On crowd favourite – the combined Native and Scar exhibitions by Michael Jalaru Torres.

Michael Jalaru Torres is a Djugan and Yawuru man with tribal connections to Jabirr Jabirr and Gooniyandi people. He’s from the Kimberley region, and currently works and resides in Eltham, Victoria.

For the last two years at Head On, Michael has had solo shows in the Featured Program – Scar in 2018 at the Festival Hub, and Native in 2019 at the Cooee Art Gallery. Both exhibitions were highlights in Inside Imaging‘s coverage, with Native a much larger show which also brought together work from several other projects.

Moshe told Inside Imaging that a selection of images from Scar and Native were chosen for Pingyao from Head On’s expansive archive because Michael produces wonderful fine art photography that explores social and political issues about indigenous identity.

Here’s an exert from the Native exhibition description:

‘Being ‘”native” in the past was a negative experience, with a system that was designed to constantly hold down native people and take away or not recognise our rights and values. Being “native” was viewed as being literally part of the landscape, like livestock that was owned and abused.

Being “native” today reflects on the survival and resistance of not only the first peoples of this land but also the longest living culture on the planet. Culture is in a revival stage and the values of looking after country have become mainstream. Native people are at the forefront of protecting land and sea and the native animals that share this land.’

Moshe is preparing to show two more exhibitions at two Chinese photo festivals in the next few months, including the Head On Landscape Prize finalists.

A drum we’ve banged continuously is how valuable Head On is to Australian and international photography. While the festival is best-known as the major annual photo festival in Sydney, the connections with other prestigious international festivals also allows it to tour exhibitions overseas.

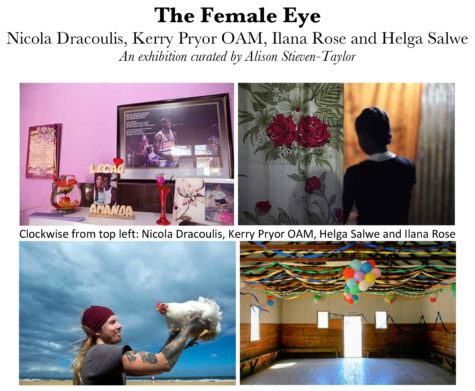

The Female Eye

The Female Eye brings together work by four Australian documentary photographers – Nicola Dracoulis, Kerry Pryor OAM, Ilana Rose and Helga Salwe. It’s the first time Alison Stieven-Taylor, a journalist and PHD candidate specialising in photography, has curated an exhibition for a photo festival and it was also her first trip to Pingyao.

‘These four artists exemplify the unique perspective that women can bring to documentary photography,’ Alison said in an article published by Monash University, where she is a PhD candidate and lecturer. ‘Each has created a body of work that is infused with their own visual signature as they explore four very diverse, yet universal themes – loss, longing, love and hope. I’ve championed Australian photographers through my work as a journalist and am thrilled to showcase the talents of these amazing women at such an important international event.’

Here’s an explanation of each project in The Female Eye, courtesy of Monash Univeristy:

Nicola Dracoulis’ long-term project Vivier no Meio do Barulho (Living in the Middle of the Noise) captures the lives of nine young people living in Rio’s notorious favelas. Seven years after the first portraits were taken Nicola returned to discover how their lives had changed.

Kerry Pryor’s The Lost Generation conveys the toll that AIDS, famine and conflict have inflicted on Ethiopian families. Her pictures, quiet and thoughtful, speak of the loss of an entire generation.

Ilana Rose’s This Chicken Life is an irreverent and joyful celebration of chickens! These playful portraits capture the “chooks” and the Australians who love them, creating a quirky, yet relatable narrative on relationships.

Helga Salwe’s Mother Country features images that are intensely personal, and talk of isolation, both allegorical and literal, and the desire to escape.

Alison also gave a guest lecture at the PIP education symposium.

Lastly, Inside Imaging understands that RMIT had a show called Transitions, and that the university regularly takes students work to Pingyao.

But we haven’t stumbled upon much information about the show, and there may well have been more Australian photographers showing work at PIP.

While it took some effort to track down the PIP website, after many failed attempts on Google (for some reason SEO and Google juice isn’t of much value to the Chinese), an English translation of the website couldn’t properly format and reveal the full program.

So if we missed something, let us know in the comments below and we’ll update accordingly.

Be First to Comment