Adobe, The New York Times, and Twitter have developed a new photo metadata prototype that will provide everyone access to data about the ‘source of visual content and how it was edited’.

The collaboration is called the Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI), which aims to create a digital image file ‘attribution-focused solution’ to prevent ‘inadvertent misinformation or deliberate deception via disinformation’.

It will use ‘cryptographic asset hashing to provide verifiable, tamper-evident signatures that the image and metadata hasn’t been unknowingly altered’. Cryptographic asset hashing is a mathematical process used with cryptocurrencies and password storage that is apparently very secure and cannot be tampered with.

CAI has brought in photo verification platform, Truepic, to handle this crypto blockchain side of the business. The company has existing technology that uses crypto-related solutions to ‘protect the integrity of… captured information’.

Right. Some folk will now likely be scratching their heads in confusion at the CAI’s opaque terminology, so let’s break it down in layperson’s terms…

The metadata of the future?

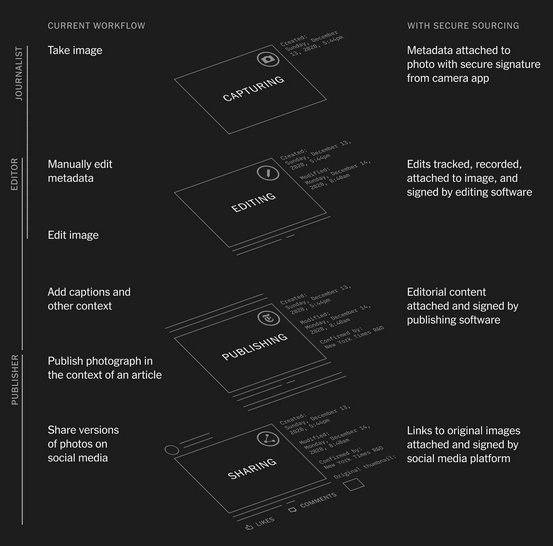

There will have to be widespread adoption of the new CAI technology. This requires camera companies, image editing software developers, news organisations, photojournalists, and others to opt in and enable the technology to work on their equipment.

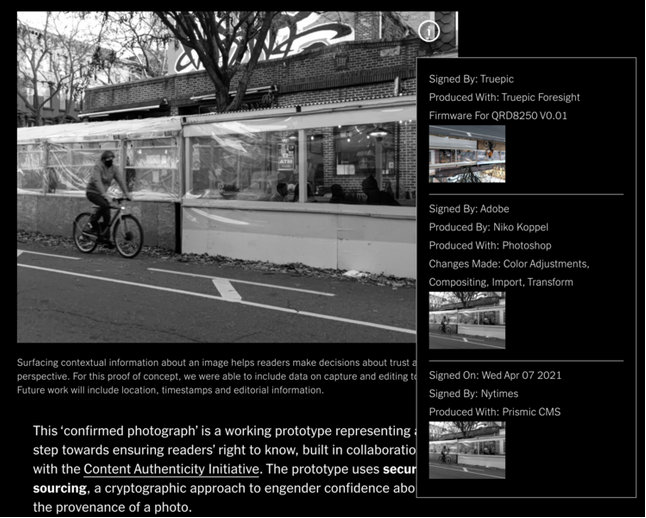

The result is each process – from a photojournalist capturing an image, a picture editor making adjustments, through to publishing an article and posting to social media – will be recorded, signed, and stamped. A ‘confirmed photo’ icon then appears on the image, and users are able to access a database with all the recorded information.

If a picture editor crops and adjusts the colour of an image, the post-processing software signs off on these changes and it will become publicly available.

Santiago Lyon, photojournalist and CAI head of Advocacy and Education, explains this is an industry response to a major issue facing online image manipulation.

‘…We (The New York Times) sometimes receive doctored images, conspiracy theories, and fake news from outlets disguised as news organisations; content produced to further an agenda or simply to make money from advertising, should it go viral,’ he wrote in a blog post.

‘Regardless of source, images are plucked out of the traditional and social media streams, quickly screen-grabbed, sometimes altered, posted and reposted extensively online, usually without payment or acknowledgment and often lacking the original contextual information that might help us identify the source, frame our interpretation, and add to our understanding.’

Metadata is the ‘long-established’ standard for image file attribution, and this information is easily altered by a third-party. Social media platforms often strip away metadata from uploaded photos, for instance. Overall it’s an ‘imperfect and inefficient’ attribution system, according to CAI, that forces ‘content moderators, fact-checkers and end-users… to reconstruct context’.

Speaking about the new industry standards, Lyon says it’s ‘a major step forward in the work we’ve forged with our community of major media and technology companies, NGOs, academics, and others working to promote and drive adoption of an open industry standard around content authenticity and provenance’.

The CAI states its specifications must be reviewed with a critical eye, as there is potential to misuse or abuse its system. Additionally, providing complete transparency about when and where an image is captured can cause unintended harm, such as ‘threats to human rights’.

Here’s an example of how the technology could curb misinformation.

When the 19/20 Black Summer bush fires engulfed the Australian east coast, visual content from the natural disaster went viral on social media. There were powerful photos of people taking refuge on beaches, kids being whisked away to safety in boats, animals escaping the inferno, firefighting efforts, and the tragic aftermaths. One viral image showed an elderly woman and her grandchildren sheltering under a jetty. This image was captured in Tasmania in 2013, and without context it fit perfectly into the visual narrative. Inside Imaging identified the image’s mistaken identity as it received a Special Mention in the 2014 World press Photo Contest.

A rock solid and secure metadata database, such as the proposed prototype, would create a more efficient system to determine the origins of the image. While it seems unlikely the masses on social media would bother to check before sharing, the CAI technology is a better authentication system than what’s currently available. It may also assist photographers when it comes to tracking images and protecting copyright.

Here’s how the CAI describes a photojournalist’s new workflow:

1. A photojournalist uses a CAI-enabled capture device during a newsworthy event they are covering. The photojournalist will set the capture application to the preferred settings of the outlet (i.e. authorship, geolocation, time, file storage preference) and register their identity via the device. The photojournalist then captures images from the newsworthy event with CAI capture attribution details included.

2. The photojournalist then moves their files from a capture application into a photo editing application (e.g. Lightroom, Photo Mechanic, Capture One, etc.). The photojournalist will ensure that the editing application has CAI functionality enabled with the proper settings and manually add metadata about subjects and context as well as complete some light editing.

3. T he photojournalist then sends their assets and captions to the appropriate photo editor of their publication. The photo editor opens the assets in a digital imaging tool (e.g. Photoshop), verifies the incoming CAI provenance data, and checks that the data meets editorial standards. The editor then makes edits in accordance with their posted photo editing guidelines. The photo editor ensures they are utilizing CAI-enabled applications with the appropriate settings throughout their work to ensure that their editing actions are captured and documented.

4. The photo editor works with others to finalize the article to be posted on the website of the news organization. The asset is moved into the content management system of the news organization, which has a CAI implementation so that journalistic context can be displayed and carried through to the website. The article is published.

5. The social media manager then posts links to the article on various social media platforms. While social platforms may alter the asset by, for example, compressing and cropping, the CAI metadata survives these alterations. In fact, these modifications would be added to the CAI data captured in the preprocessing pipeline of the social media platform. The resulting post is CAI-enabled and provides consumers the ability to learn more details about the asset (e.g. Who took it? For what publication? When did they take it?).

6. As other social platform users continue sharing the asset (thus disconnecting it from its original affiliation with the media outlet), CAI data will travel with the asset and any user who sees the asset posted by any other user, will be able to investigate the source and original context of the asset.

7. As required, various analysts from fact-checking organizations will verify the CAI data present in the asset, correlate it to any associated article, and then add their own labels and clarifications to it. Together this collection of CAI data creates a rich, verifiable context that amplifies confidence in the authenticity of the asset.

Adding copyright, licensing and credit to the blockchain would help prevent orphan works.

Isn’t blockchain technology extremely energy hungry, requiring huge computer power? Well that’s what is said about bitcoin blockchain technology. Or is there a better way to apply it in this instance?

the power consumption comes from intense processor use doing bitcoin mining which requires massive amounts of number crunching. The blockchain tech is kind of like a different and unique file type, or a lock and key with just the one key, so has almost no impact on power use. We will see this technology everywhere, whether we know we are using it or not.

I must say, this is a clever and unexpected application of the technology, though perhaps a bit late to the game, though deepfake tech (among others) has really brought the need for it to a head