AI image generators are being used to create photo realistic representations of newsworthy events, leading to concern that the new technology is threatening the integrity of photojournalism.

There is curiosity about how the new AI text-prompted image generators like Midjourney and OpenAI’s Dall-E can be used in a valid way, with various experiments exploring the limits of the powerful technology.

Guidelines on the ethics of AI photo realistic imagery are yet to drafted, and each widely-publicised AI stunt flares up debate about what is right or wrong. By far the biggest buzz was created by German photographer, Boris Eldagsen, who won the Sony World Photography Awards Open category with an AI image.

Meanwhile two other AI photo realistic projects came and went without causing much of a stir. Which is surprising, as both projects push the boundaries of ethics and good taste to the brink by filling a photojournalism-shaped hole with AI images.

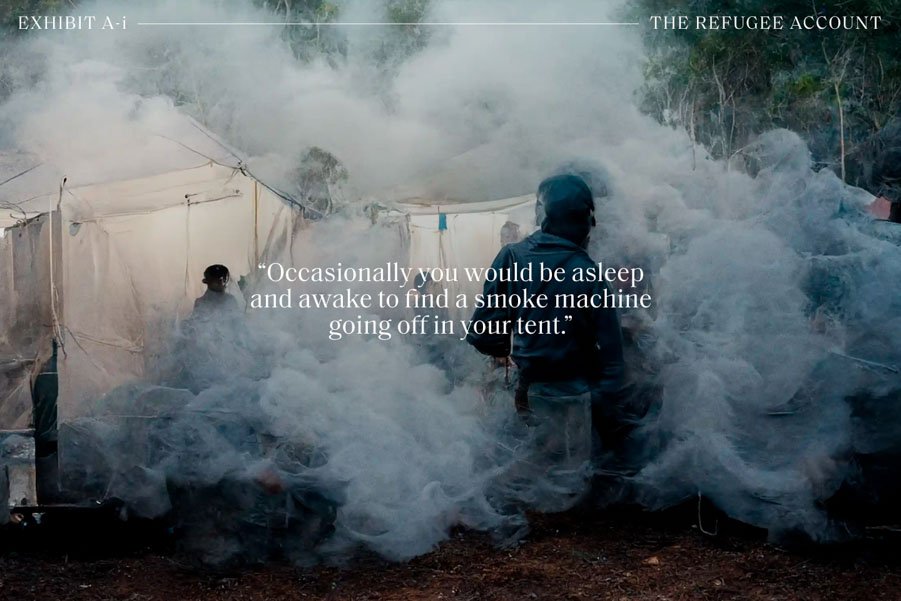

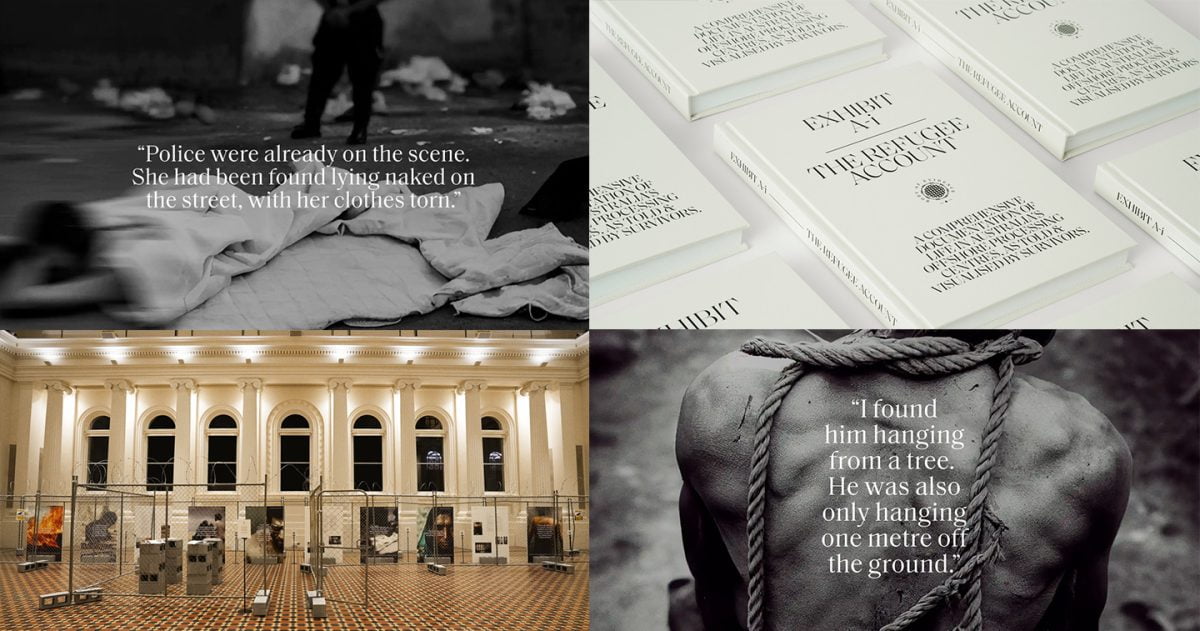

In early April Maurice Blackburn Lawyers announced Exhibit AI: The Refugee Account, a ‘photo-journalistic visual account of life in offshore detention’ based on the accounts of 32 asylum seekers; and respected US National Geographic photographer, Michael Christopher Brown, launched 90 Miles, a commercial NFT project he describes as a ‘post-photography, A.I. reportage illustration experiment’ showing Cuban migrants fleeing the country.

‘Photojournalism aims to be 100 percent accurate and representative of the story you’re trying to tell,’ award-winning photojournalist, Brian Cassey, told Inside imaging. ‘That’s the line between photojournalism and any other photographic discipline. … With AI it’s not a fine line. It’s a chasm. As soon as faith is lost in photojournalism, we’re in big trouble.’

Some of the AI images are disturbing, and show self harm and violence. A reminder they are not real. Although the images are based on witness testimony. And the AI image generators are trained by scanning millions of ‘real’ images, often without the author’s consent. Who knows what dark corners of the web Midjourney scanned to fine tune it’s depictions of violence.

‘Truth telling through AI’ – really?

Exhibit AI’s creators fed portions of the asylum seeker witness statements, previously collected by Maurice Blackburn Lawyers for a now-discontinued lawsuit against the Australian Government, into the Midjourney AI image generator.

‘This was important as there was limited to no access for journalists and camera equipment on Nauru and Manus Island, meaning there was no visual documentation of Maurice Blackburn’s clients’ experiences,’ states the press release, titled ‘Truth Telling Through AI: Largest Collection of Offshore Detention Witness Statements Released‘.

Gavin Chimes, Howatson+Company executive creative director, claims the agency ‘implemented a rigorous process’ to ensure the images were accurate. They isolated a key section of the statement, and input ‘key words’ into Midjourney to create ‘our first draft of the image’.

‘The images were then workshopped with the survivors of offshore detention to ensure the depictions of their experiences were as accurate as possible,’ he said. ‘From the colour of tents to identifying the foliage native to the island on which they were detained, to the expressions on the guards’ face – each detail was meticulously scrutinised and tweaked accordingly to reflect the lived reality of each person’s experience.’

Inside Imaging asked Brian, who has photographed asylum seekers on Manus Island three times and often works in the region, whether the AI images appeared familiar to what he witnessed.

‘Nothing like it,’ he said. ‘I know the Detention Centre – it’s a navy base and I’ve been several times. Both in and on the outsides. In a generic sense the images also don’t ring true.’

Brian was disturbed by an AI picture showing a silhouette of a man hanging from a tree.

‘Really can’t stress how obnoxious this particular “image” is – yes so are others, but this one takes the bloody cake. Obviously constructed for shock value alone – it also bears absolutely nothing in common with detention centres in Papua New Guinea and the Pacific, or the comment they have attributed it to. To me it seems to be set in misty north America or Europe. Nothing even vaguely says Manus or Nauru detention centre. It is a totally offensive construction that will influence viewers and depicts to them a massive lie.’

While Maurice Blackburn Lawyers and Howatson+Company are transparent about using AI, they cosy up to the idea that the project ‘resembles photojournalism’ and fills a ‘truth’ hole.

An accompanying video does an impeccable overreach by projecting the AI imagery as iconic. It begins by stating ‘the most powerful evidence in history is visual’ and ‘the right image not only exposes injustice but can help put a stop it’. The video juxtaposes the AI pictures with three famous images: Arthur Tsang’s Tank Man, Wayne Ludbey’s picture of indigenous AFL player Nicky Winmar, and Bill Hudson’s photo of a 1960s US civil rights activist being attacked by a police dog.

Exhibit AI brought in Walkley award-winning photojournalist, Mridula Amin, who has worked on Nauru, to work on the project with AI technicians. She did not respond to Inside Imaging‘s request for comment.

‘Photojournalism is so raw and visceral,’ she states in the video. ‘The heart of this project is making sure that these witness statements are honoured and having the impact they deserve.’

In the press release, Mridula equivocates on the project’s association with photojournalism, instead describing it as ‘being supplementary’ and opening ‘an exciting door into new ways of visual storytelling, especially when real photography isn’t possible’.

Gaining access to offshore detention centres is incredibly difficult. The last time Brian Cassey visited Manus Island – days after the Australian government abandoned the facility – he was smuggled over by asylum seekers and only stayed for 18 minutes.

Despite acknowledging the lack of access, Brian finds the argument is flawed. In his view, the pictures cannot accurately reflect reality, regardless of rigorous ‘workshopping’ with witnesses.

‘It’s disgraceful to come up with that argument because it’s going to be manipulated for their own means,’ Brian said. ‘It will show what they want to show – not what reality is. There is an argument in photojournalism that as soon as you take a photo, you change the scenario, but at least it’s a hundred thousand times more accurate than constructing an image using AI.’

Commenting on Michael Christopher Brown’s Instagram post displaying the 90 Miles AI images, Matthew wrote: ‘This is a fantasy that reflects your world view. By associating these fictions with the traditions of photojournalism, you have further blurred the lines in an age of fake news’.

Although Matthew has ‘mixed feelings’ about the Exhibit AI project as ‘it’s a form of activism and is a way to communicate what we’ve been told happened’ by a group that’s ‘not beholden to journalistic ethics and integrity’.

‘I know that many organisations in the past would have relied on illustrations to tell the same story. In my view illustrations are great,’ he told Inside Imaging. ‘They’re emotional, high impact, and show what you need to show. But the audience has an understanding that this is a creation based on a testimony. There are no blurred lines that this is a re-creation. For me it’s the perfect balance. And I’ve definitely been emotionally affected by looking at illustrations – there is no reason why it can’t have that same emotional impact as photography.

‘But I feel conflicted because it’s trying to recreate something as a reality, and is clearly based on testimony. It’s not an actual depiction of the event itself. In that sense I don’t think it’s a good direction to be heading down, but there are no laws against it, and if these groups feel this is a way for them to lobby and engage people about these issues, then that’s their choice.’

Freelance photojournalist and film production stills photographer, David Dare Parker, shares Brian’s concern, but like Matthew is in two minds.

‘One concern is that by creating something that looks this real, it could be misconstrued as having been documented by an actual photojournalist, and could be offered up as truth of evidence,’ he told Inside Imaging. ‘If the imagery was derived from the actual eye witness testimony, perhaps it could be considered something akin to police sketches or court drawings? That image of the guards is an emotive cliché of evil, but is it a truthful representation of the event itself? I would prefer to listen to, or read an actual witness testimony – any day over this.

‘Reality TV/film and documentaries often use re-creation for context and to garner emotion and empathy – so maybe there is a place for this – as long as there is full transparency and disclosure.’

At no point does the material supporting Exhibit AI attempt to divorce the images from photojournalism, which could perhaps be achieved by describing them as ‘artistic renditions’, ‘illustrations’, ‘interpretations’, or otherwise fictitious. [Editor’s Note: Exhibit AI has since added a disclaimer that the images are not real and are generated using AI technology.]

Matthew worked on Manus Island for Australian political activist group, GetUp!, which requested photos showing the faces of people living there. This was because the majority of Manus Island Detention Centre imagery came from government, which was ‘always captured in a way where it never showed humanity’.

‘Either with harsh light or dark faces – you’d never see faces or expression. No smiles or humanity. The idea of this project was to go and show these are real people that live here. Clearly they’re [Maurice Blackburn Lawyers] trying to do a similar thing, but there is a lack of access for journalists. And if that’s the case, how much credibility do these images have?

‘And will it mean that, in the future, photojournalists are less inclined to take huge risks to go and report on the truth?’

He adds that another issue is if people become conditioned to viewing AI pictures that show ‘extraordinary fictions’, they may be less moved by imperfect photojournalism of real situations.

Ben Handberg, Howatson+Company head of PR, cribbed passages from the press release to quote to Inside Imaging when asked about the potential ethical issues about the project’s association with journalism.

‘It’s important to note that the witness statements from Maurice Blackburn’s clients about their time in offshore detention are the central part of the project,’ he said. ‘These people wanted to find a way to bring to light their experiences offshore. They were very clear that they wanted any images to be in line with their recollection of their time on Nauru or Manus, and to do justice to their story.

‘As there were no cameras or journalists allowed, using AI technology was the best way to do this. It enabled the clients to provide feedback on the images generated so that they could be fine-tuned to more accurately represent their experience.’

He adds that the ‘refugees were heavily involved in the creative process’ and ‘felt empowered by this project which helped them contribute to a visualisation of their life in offshore detention’.

‘Importantly, while photojournalistic in style, the project is very clear that these are AI-generated images, and they were only required because journalists were not allowed on Nauru or Manus Island in the first place.’

No watermarks to confirm their AI generation, though.

Check out Exhibit AI here.

MCB ‘mints’ AI NFT

While Matthew has mixed feelings about Exhibit AI, he’s much more concerned with the direction taken by Michael Christopher Brown with 90 Miles. The project explores ‘historical events and realities of Cuban life that have, since 1961, motivated Cubans to cross the 90 miles of ocean separating Havana from Florida’.

‘It’s disappointing really to see someone of his calibre and weight in the industry going down this path,’ Matthew said. ‘One of his justifications is he wanted to photograph it but couldn’t get access. And so this is an alternative. That’s all very well, but my concern is that someone of his background and position in photojournalism – it just sends the wrong signal.’

Michael is selling 400 unique NFTs made using Midjourney AI text prompts for 0.1 [US$1795] Ethereum cryptocurrency per piece. He’s pocketing 90 percent of the profit, with 10 percent donated to charities working with Cuban refugees.

In the 90 Miles project description, Michael states he’s always been influenced more by mythology and art history than photography. ‘…and now, after 25 years of working mainly as a photojournalist, through A.I. that inspiration is returning to my imagination.’

‘Publications such as The New York Times and The New Yorker have for decades used reportage illustrations of various kinds alongside reporting, to illuminate experiences, ideas and people in various ways while expanding our idea of a subject,’ writes Michael. ‘Reportage illustrations allow for fresh connections to something that, though the illustration may not be real, may feel true.

What he calls ‘A.I. Reportage Illustration’ ‘may arguably go a step further, as a generated image created from hundreds of millions of photographs may feel not only true, but real.’

Although as Matthew pointed out earlier, reportage illustrations work because they are not photo realistic. And even if a re-creation of a real event, they’re clearly not reality. On the other hand he believes that ‘we, as humans, are conditioned to read photographs as real – as reality’, and this reality now comes into question as AI enables the creation of flawless photo realistic graphics.

‘I was shocked by the MCB post,’ Matthew said. ‘I felt, maybe naively, relieved that I was a photojournalist and not in another space like advertising, where those [AI] images can ethically be created. There is no real reason why not. I was vaguely hoping that this could maybe be a renewed time for photojournalism, because it could reinforce how important reality is – real images.’

Michael, a National Geographic photographer since 2004 and former Magnum associate, is best known for photojournalism, but he also describes himself as an ‘artist’.

View this post on Instagram

The 90 Miles NFT project was launched via Instagram in early April, with Michael stating upfront that ‘THIS IMAGERY IS NOT REAL’. Despite the odd positive response, the vast majority of photographers are highly critical of the project.

Here is a selection of comments:

‘I am sad I got sucked into this,’ wrote National Geographic photographer, Paul Nicklen. ‘I have always loved Michael’s work. Big fan. I should have read the caption. This is shameful to our industry and to Michael. Shit!!!’

US photojournalist, Sara Diggins, wrote: ‘Profiting from… degrading the profession of photojournalism? From stealing others artwork? From damaging the environment? From people’s trauma and suffering THEY DIDN’T EVEN GRANT YOU ACCESS TO ?! This is wrong on so many levels and you need to stop before others follow your lead.’

‘Could’ve just collaborated with a Cuban artist/painter and made similar or even more interesting work,’ wrote US freelance photographer, Peter Fisher. ‘But when you need cash fast, real people are just too damn slow lol.’

‘Imagine if I made a series of images based on a traumatic experience in your life using Midjourney, then tried to sell them as an NFT and took 90 percent of the profits and gave you 10 percent. As someone who experiments with AI, I think it’s interesting to explore this technology and not shy away from what’s coming next, but to attempt to profit off of your imagined view of a culture that you may not truly understand is not okay. Please take some time to be introspective about this and do better next time.’

It goes on for more than 600 comments on a single post, likely the most engagement Michael has recently received on an Instagram post.

One of the few photographers to defend Michael is James Whitlow Delano.

‘You are getting dinged up on this and I kind of understand why and kind of don’t. I have spoken widely about my concerns about the propaganda potential of AI. This is different. You are open and transparent about what you are doing. It is kind of like a historical fiction cinematic graphic novel. A graphic novel is not journalism and it is not documentary. It is a fictional representation of historical events or whatever plot it wants to lay out. This kind of reminds me of “Apocalypse Now”, an adaptation of “Heart of Darkness” to comment on the Vietnam War, when “Heart of Darkness” itself was a fictional story to comment on the atrocities in colonial Belgian Congo. Without your transparency, there would be a problem but you make it clear this is fiction.’

Both 90 Miles and Exhibit AI clearly aim to benefit from the hype du jour around AI image generators to gain more publicity. This thirst for attention can be a double-edged sword, as Amnesty International recently found out. The human rights advocacy group recently deleted a series of AI generated images depicting police brutality against protesters in Colombia after facing widespread criticism.

Amnesty initially defended the pictures by stating it protects the identity of protesters, who may be subject ‘to repression and stigmatisation by state security forces’. An Amnesty International spokesperson included a disclaimer ‘to avoid misleading anyone‘.

‘The images were also edited in a way so that they are clearly distinguishable from real-life photography, including the use of vivid colours and a more artistic style to honor the victims. Amnesty International’s intention was never to create photorealistic images that could be mistaken for real life. Leaving imperfections in the AI-generated images was another way to distinguish these images from genuine photographs.’

Sam Gregory, head of WITNESS, a global human rights network, is worried that credible organisations utilising AI-generated imagery may degrade trust in real photos.

‘Human rights defenders already have images and videos undermined – don’t contribute to it by utilising AI-generated imagery in this way,’ he wrote on Twitter. ‘Yes, there will be ways to use AI-generated imagery for advocacy – this is not it.’

Amnesty Norway, which published the images on Twitter, deleted the post after acknowledging the use of AI was ‘only distracting’ from their core message to support victims.

While the guidelines on ethics and AI photo realistic imagery are yet to be drafted, it seems reasonable that photojournalism should remain off limits. Although apparently not everyone feels this way.

Editor’s Note: After Inside Imaging contacted Hotwason+Company about journalism ethics, and Amnesty International came under fire, the Exhibit AI website now includes a disclaimer stating the images are not real and have been generated using AI technology.

Potentially AI destroys the fundamental purpose of photo-journalism, reportage, documentary and the seekers after truth. Really depressing.