Lars Boering has left the World Press Photo Foundation (WPP). During his eventful five-year tenure as managing director he steered the leading photo contest/showcase toward becoming a ‘think tank’ devoted to progressive values and ethics.

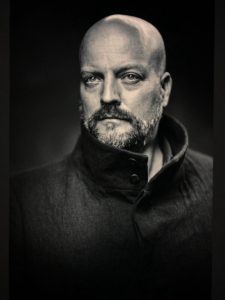

Boering (right) was appointed managing director of the Amsterdam-based non-profit organisation in January 2015, after serving the same role at Fotografen Federatie (now DuPho), an association for Dutch professional photographers.

His sudden departure has left WPP searching for an individual to fill his shoes, with an interim business director holding the role until the Supervisory Board finds a replacement. Regarding his departure, Boering says:

‘It was a tough decision to leave this beautiful organisation, especially given the timing. It has been an amazing time and I am incredibly proud of the organisation and the impact it has achieved. In these interesting and challenging times the World Press Photo Foundation, and the work it does, is more relevant now than ever before. Personally, it is time for me to pursue other opportunities, but I am confident about the future path for the organization, and am sure a successor can be identified soon.’

Boering’s vision from the outset was to build the world’s biggest international press contest into an organisation with a set of advocacy agendas. Speaking with Time Magazine in early 2015, he criticised WPP for being ‘neutral’ and not having ‘strong opinions about issues affecting photographers’.

‘I’d really like World Press Photo to become the think tank of the industry. And a think tank should invite everybody at the table to discuss – people from the photojournalism and journalism fields, but also people working in data research, visualisation, etc. It should be a mix of traditional and innovative organisations. It’s where the change is coming from. We should keep moving and keep the debate going.’

Boering was far more vocal and opinionated than his predecessor, Michiel Munneke, who held the position for over a decade. Boering penned numerous opinion articles regarding the state of photojournalism, often writing about the lack of racial and gender diversity.

In 2017 Boering wrote for the WPP Witness blog: ‘Even more worrying to me is the fact that large populations of the world are severely underrepresented in the contest. Once again this year, African entrants to our photo contest comprise only 2 percent of the total. This is unacceptable. ‘

The WPP launched a program in 2016 called the African Photojournalism Database, which lists over 180 local professional photographers available for hire. Speaking about the database, Boering wrote, ‘there should never be an excuse to say we can’t find someone local to shoot work or send on an assignment.’

Photojournalism has historically been dominated by Westerners. A few of these photographers captured iconic pictures, playing a role in informing the public on matters which may go on to shape history.On the other hand, some may argue the dominant ‘Western gaze’ can also stereotype, simplify, or miss the real issues affecting a foreign culture or subject.

Programs like the African Photojournalism Database, and various global workshops, are initiatives by WPP to provide more opportunities to photographers of different backgrounds.

‘Diversity is now one of the World Press Photo Foundation’s three core values, and we’re all engaged in the ongoing task of putting it into practice, with a global view, in all areas,’ Boering wrote in 2018. ‘Diversity – both in terms of who makes the stories, and the perspectives of those stories – is essential to the freedom of expression, freedom of speech and freedom of the press that we’re supporting at the UNESCO World Press Freedom Day event. Enabling global diversity is a constant process for all of us and one to which we are fully committed.’

The managing director is a vocal critic of male dominance in photojournalism, with him describing the 85 percent of male entrants as ‘disturbing’.

‘However, as the analysis in our 2017 Technical Report shows, we – and the industry as a whole – have a long way to go before we can be satisfied. For the last three years, women have comprised only 15 percent of entrants. And while we don’t yet know if that percentage is representative of the female population of professional photojournalism, we want to do better.’

In another article, published in Nieman Reports titled ‘#MeToo and Photojournalism: What Needs To Happen Next‘, Boering elaborates: Photojournalism has a proud history of reporting for a better world where human rights are central, and this work is more important than ever. But photojournalism is framed to a large extent by masculinity, with a competitive culture of power embraced by many in the field. In a recent interview for the NRC in Amsterdam I even described it as suffering from a macho culture.

Boering later states while photojournalism has no formal governing body to ‘legislate behaviour’, his organisation is attempting to lead by example and that starts with being transparent about the gender imbalance. He goes on to highlight WPP’s ‘protocol’ regarding allegations of inappropriate behaviour.

‘Our protocol is that when we learn from reliable sources that someone working with us has engaged in inappropriate behaviour and harassed individuals, we end all association with them the moment we find out. In the last three years, this has happened on a few occasions, and we let those individuals know why we will no longer work with them.’

In one very public and clumsy incident in 2019, it appears individuals won’t always be told why the WPP is ending association with them. Australian Gold-Walkley photojournalist, Andrew Quilty, was subject to allegations of inappropriate behaviour, and Boering informed the public that Quilty had his invitation to the Awards Ceremony cancelled. Quilty responded, ‘no allegations of inappropriate behaviour have been made known to me’, and the world was left wondering what the heck did this guy actually do? And still does to this day.

Other #MeToo events typically explain in detail the accused’s alleged actions. In some cases, there are numerous victims whose testimonies reveal a pattern of inappropriate behaviour. But the Quilty case was an anomaly and seemed rushed. For whatever reason the WPP reasoned it was okay to publicly trash the Gold Walkley winner without explaining why to anyone, including him.

At the time, we wrote: ‘Swift and unforgiving punishment meted out to any individual should surely be accompanied by a statement informing both the person and the public why that punishment was justified. In this instance we don’t even know what Quilty has been accused of, let alone if the accusation has been investigated. Instead there’s a troubling situation where a range of organisations have thrown Quilty, one of Australia’s finest contemporary conflict photographers, under the bus, but are not willing to say why they have decided to do so.

‘It’s baffling the upper echelons of journalism have approached the issue this way. Their treatment of Quilty indicates that they have scant regard for the notion of natural justice.’

The last Inside Imaging reported on the matter, Quilty had engaged a team of defamation lawyers to take action against WPP. It remains ongoing.

WPP fights manipulation

In 2013, allegations surfaced regarding excessive post-processing by Swedish photographer Paul Hansen, who won the WPP Photo of the Year for an image of a burial procession in Gaza City.

Hansen’s name was cleared after the WPP commissioned an independent forensic investigation, but the controversy demonstrated to WPP it needed to flag excessive digital manipulation before awards are handed out.

In 2015, when Boering became director, image manipulation became a much bigger story when it was revealed 20 percent of finalists were disqualified for unethical post-processing.

‘In this case we found a lot and that was very disappointing. It is about trust, about the basic ethics of journalism,’ Boering said. ‘These images should be genuine and real; we have to be able to trust the photographs they put in front of us…. Of course we all know that photographs never show everything that’s going on, they are always an interpretation, but we have to know that photographers are showing what’s going on in the world.’

That year there was another unexpected bombshell. Italian photographer, Giovanni Troilo, was accused of staging images in his series that won the Contemporary Issues category. The mayor of a town Troilo photographed said his images ‘distorted reality’ and were ‘anything but photojournalism’. The WPP went into damage control mode, initially concluding there was ‘no grounds for doubting the photographer’s integrity’, and a second investigation found Troilo submitted ‘falsified information’.

‘The World Press Photo Contest must be based on trust in the photographers who enter their work and in their professional ethics,’ Boering said. ‘We have checks and controls in place, of course, but the contest simply does not work without trust. We now have a clear case of misleading information and this changes the way the story is perceived. A rule has now been broken and a line has been crossed.’

The WPP exhibition was rejected from being shown at Visa pour l’Image in France due to the incident.

In 2016, another 16 percent of photojournalists in the penultimate round were disqualified for digital manipulation. An excuse from a number of entrants, Boering said, was they mistakenly entered images that were intended for a gallery show rather than journalistic purposes.

The alarming number of disqualifications may reflect on the broader issue regarding press photographers enhancing images to deviate from ‘the truth’, but it may also relate to challenges faced by WPP judges tasked with picking award-winning photojournalism. There could be a tendency to gravitate towards documentary photography with artistic merit.

As WPP managing director, Boering had a clear vision for what he wanted the organisation to become. But at the end of the day, the raison d’etre of the organisation is the prestigious World Press Photo Contest, which ultimately reflects modern day photojournalism. In both its glory and imperfections.

Not enough WPP controversy for you? Here’s more we’ve covered!

– World Press Photo places terrorist murder on ‘high pedestal’

– World Press Photo awards ‘fake news’

Be First to Comment