A ‘found photography’ project seeking to return vintage Japanese studio and family photos, discovered in regional Victoria, to their rightful owners has sent concluded with a happy ending.

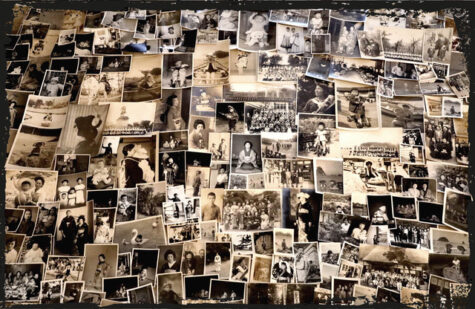

Untitled.Showa mobilised Australian and Japanese audiences to find answers. But the de facto custodian of the pictures – Sydney photographer, Mayu Kanamori, who found the 340 black-and-white pictures in 2015 at a flea market in Daylesford – is left with more questions than answers.

Mayu is a Japanese-born photographer who emigrated to Australia in her youth to study philosophy in Melbourne. Respected curator, Sandy Edwards, describes Mayu as having a deep interest in the power of photography to tell stories, with her work exploring ‘the interconnections between Japanese and Australian histories’.

This makes her discovery of the Japanese pictures, stuffed carelessly into plastic bags and sold among vintage the trinkets and knick-knacks at the Daylesford Mill Market, is either fate or a stroke of luck.

‘These kind-of photos – you know, old photographs in bags – they’re just everywhere,’ she told Inside Imaging. ‘I’ve seen them in other places. Usually it’s local Australian photos, but it just so happens they were Japanese and it caught my interest.’

When Inside Imaging covered Untitled.Showa in April 2021, shortly after the project launched, the odds of linking the pictures with their subjects seemed low. The stall holder selling the photos knew almost nothing about the images. Only that they came from a deceased estate in Geelong, Victoria.

‘Most were taken in the 1950s and 1960s but others were much older, including those of men in military uniforms from WWII, and some portraits from the 1930s or earlier,’ Mayu wrote in a blog post. ‘The same people appeared in different situations, giving the impression they were from one family.

‘Some featured workers from a film studio in Kyoto where director Akira Kurosawa’s famous film Rashomon was shot in the early 1950s. There was writing on the back of some of the prints, along with a few letters and postcards written in Japanese and official documents such as school identification cards and pay slips.’

The photos aren’t of a high creative calibre. This isn’t another Vivian Maier story of an incredibly talented but unknown photographer. Studio and family photography was also common in post-war Japan, and it had one of the largest populations at the time. Yet something about the photos, the unknown story and the project captivated Mayu and others – including Japanese journalists, as well as Australian and Japanese audiences – leading to a cross-continental effort to find the subjects.

The pictures were captured by more than one photographer, but one individual appears to have shot the majority of them. This person may link the various studio photos together, or it’s possible someone unrelated to somehow collected the photos to bring them together.

‘A lot of the images that we returned were related to photography studios,’ Mayu said. ‘We were able to identify them either by an embossing on the photo with the name of the studio, or an encasing. As for the other pictures, there is one group of subjects who frequently appear in them. I don’t think what we’re seeing is their art collection, but an ordinary photographer taking family photos.’

To launch the project, Mayu and web developer, Chie Muraoka, built a English/Japanese bi-lingual website to showcase the images. Sandy Edwards came onboard as art director to organise workshops and exhibitions in Sydney, Geelong, Adelaide and Kyoto.

Lines of communication were then open for people to provide potential leads about the pictures, and this resulted in plenty of dead ends.

‘It could be hit and miss. It certainly sparked some peoples’ imaginations,’ Mayu said. ‘Something in it really engaged with people. And there was plenty of work to follow up.’

It was the Kyoto exhibition which first led to positive results. Prints were shown at stores along the Daiei Shopping Street, named after the major Daiei Film studio that regularly appears in the collection.

‘Instead of having it in a gallery, we had pictures appear in participating shops along the street. It was good because it raises larger community awareness than having it in one gallery, and that produced out first positive lead.’

A shop owner saw a picture of a woman they knew, who once owned a restaurant in the area. They tracked down the son of this restaurateur, who had moved to the Nagano prefecture. ‘He went online to visit the gallery, and indeed it was his mother but there was also many photos of his aunt, who worked at the Daiei studios.’

This resulted in 15 photos being returned to the family with the son/nephew, Akihiko Yamamoto, ecstatic to receive the photos and participate in the project.

‘On the following day [he received them], they were placed on the alter in time for a Buddhist ceremony for his aunt’s third year anniversary of passing – an important day marked in the Buddhist calendar.’

There were other success stories, with the Akita Sakigake Shimpo newspaper’s coverage of the story leading to contact with photo studio owners or relatives. One story reunited a picture, likely shot between 1930-41, with a photo studio in Noshiro that had been operated by the same family for four generations. An elderly man, whose descendants continue to run the studio, recognised details that suggested it was captured by his father or grandfather.

Who owns the photos?

Mayu was challenged by the concept of ownership in regards to found vintage photography. While the copyright holder, or their estate, is the owner by law, an old print may only be of value to the portrait subject and their family. For instance, if someone’s great grandfather was a professional photographer and captured a portrait of a client’s family, the great grandchild of the photographer may be puzzled why they are the custodian of the image. However, the great grandchild of the subject in the photo is likely to have a sentimental connection with the photo.

And then there is the individual who came into possession of these photos in Japan, and felt it worthy to take them to Geelong. And Mayu, another custodian, spent considerable time and effort making sense of the photos, and has established her own connection with them through the project.

‘This process, from a photographers point of view, brings about a lot of questions. More questions than answers about one’s own photograph archives and family photos. Who does the image belong to? We’ve seen this found photo stuff before. Vivian Maier being the most well known. It all seems to centre around who the photographer is. But I feel we’re exploring notions that we’re all now custodians of images, as opposed as anyone strictly owning the copyright.’

Beyond returning the photos, Untitled.Showa ran workshops to discuss the project and found photography more broadly. As it was an ‘experimental’ project, Mayu often asked workshop participants how they felt the project should conclude.

‘The opinion was split between participants thinking we have to hand deliver the photos and document it, versus simply returning the photos via mail. There was an interesting discussion about whether we need to document everything. If we genuinely want to return it, we return it. We found something, we return it.

‘Or do we need to hand deliver it and make a film? People in the creative arts, whether they’re photographers, filmmakers or artists felt it needed to be returned by hand and documented. Those who weren’t necessarily in the creative areas had the viewpoint is that returning it is enough. Some also felt it’s not just about documenting it, but witnessing the return.’

Mayu also discovered that while she and others were excited to return the photos, sometimes the recipients didn’t quite share the same level of enthusiasm. One individual said ‘thanks, but no thanks, I’ve got enough family photos and am trying to have less stuff’.

After running exhibitions and workshops in Australia and Japan, and returning handfuls of photos to Japanese custodians, Untitled.Showa has come to its end.

While it would be an even more ‘complete’ project to find out how the images ended up in Geelong, there’s a real possibility it might not be a poetic or romantic story. It’s could even be a bit of a fizzer. Perhaps an Australian traveller found the random photos jumbled together in a Japanese flea market, and bought them home to Geelong as a souvenir.

Sometimes questions are better left unanswered.

Be First to Comment