US airline, Delta, is harvesting customer’s images for free, by dubiously claiming anyone posting photos to Instagram with the hashtag #SkyMilesLife provides them a perpetual image licence.

![]() American photographer, David Bergman, noticed the #SkyMilesLife advertisement on billboards at airports encouraging travellers to post images with the hashtag, to potentially have the image shared on Delta’s social media channels.

American photographer, David Bergman, noticed the #SkyMilesLife advertisement on billboards at airports encouraging travellers to post images with the hashtag, to potentially have the image shared on Delta’s social media channels.

‘With travel inspiration at your fingertips, you can explore thousands of photos taken by other SkyMiles Members who are living their best #SkyMilesLife around the globe. Follow #SkyMilesLife on Instagram to get inspired and plan for future travel through the eyes and experiences of real SkyMiles Members.’

Bergman then noticed the fine print in the Terms and Conditions is a complete rights-grab, and shared it to social media.

‘By tagging photos using #SkyMilesLife and/or #DeltaMedallionLife, user grants Delta Air Lines (and those they authorize) a royalty-free, world-wide, perpetual, non-exclusive license to publicly display, distribute, reproduce and create derivative works of the submissions (“Submissions”), in whole or in part, in any media now existing or later developed, for any purpose, including, but not limited to, advertising and promotion on Delta websites, commercial products and any other Delta channels, including but not limited to #SkyMilesLife or #DeltaMedallionLife publications

User grants to Delta (and those they authorize), the irrevocable and unrestricted right to use, re-use, publish and re-publish, and copyright his or her performance, likeness, picture, portrait, photograph, in any media format, in whole or part and/or composite representations, in conjunction with my name, including alterations, modifications, derivations and composites thereof, throughout the world and universe for advertising, promotion, trade, or any lawful purposes.’

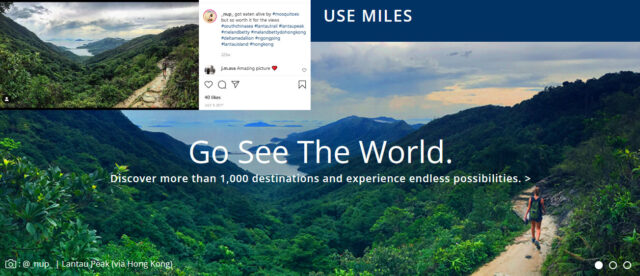

Sometimes these rights-grabbing T&Cs are unintended mistakes, potentially attributable to drafting a concrete set of clauses to ensure the company isn’t at risk of being liable for copyright infringement. Delta, however, hasn’t just re-shared the Instagram images on social media, but gone ahead and published them on its website.

This method for building a free photo library has been around since hashtags became a thing, and in Australia it’s regularly implemented by government tourism agencies.

In 2017 Inside Imaging reported how government-owned agency, Tourism Tasmania, published Instagram photos on digital billboards at the Hobart Airport without permission the copyright owners, who used the generic hashtag, #DiscoverTasmania. After landscape photographers like Jason Futrill and Cameron Blake had their photos re-posted without permission, the government agency apologised and removed the billboards.

Hamilton Island, a private agency, adopts a similar ‘tag and share’ approach to social media. Apparently anyone who posts an image along with generic #HamiltonIsland tag provides the Whitsunday tourism agency permission to re-post, and this has become an integral component to its marketing strategy.

Tourism NT also ran an Instagram photo contest called ‘Snap The NT’, whereby photos were entered using two hashtags and tagging the agency’s Instagram handle. All entrants, according to Tourism NT, provided the agency an ‘exclusive, perpetual, worldwide license’, and all moral and intellectual property rights were waived.

These T&Cs stand on shaky but apparently untested legal ground. Since there hasn’t been a copyright ruling tackling the issue, it’s unclear whether companies can imply a contract is signed by a social media user using certain hashtags especially when they’re generic. Hashtags also move in trends, meaning some users simply copy what others post without knowing the origins or underlying agenda to them. Given many, if not most, Instagram users aren’t reading the third-party website T&Cs when posting a hashtag, how can it then be argued they agreed to them? There is no box to check, or direct contact asking permission to re-publish the photos. It may ultimately be considered an unfair or unconscionable contract, and potentially copyright infringement.

Regardless of the legality, it’s beggars belief this free image harvesting strategy isn’t misleading to users. They’re first and foremost under the impression their photo is simply re-posted on social media, and aren’t likely privy to the hidden agenda buried in the T&Cs.

And, of course, these initiatives devalue professional photography, as traditionally these organisations would pay for an image licence.

Speaking with Petapixel, the National Press Photographer’s Association general counsel Mickey H. Osterreicher, described these rights-grabs as an ‘overreach’.

‘It’s unfortunate that once again that far too many people devalue photography,’ he said. ‘What is wonderful, obviously, is that certainly because everyone has a cell phone and therefore everyone has a camera, everyone can take pictures, but that doesn’t make everyone a photographer — but that also doesn’t mean that their images don’t have value.

‘Clearly if there wasn’t value to these images, why would they be asking for them and these rights?’

Delta’s T&Cs also require the, uh, hashtagger to declare they are the copyright owner of the image, so they can transfer the ‘power and authority to submit… and to grant Delta the rights to… the worldwide copyright.’ And if Delta just so happens to commit copyright infringement by publishing an image that’s not owned by the Instagram user, the user who wrongfully attributed themselves indemnifies Delta from any liability.

Agrimaster, an agricultural software company in Australia, has recently done a similar thing – claiming that by using the generic hashtag #agrimaster the person who posts the image gives permission for the company to use the image for a variety of commercial purposes. There is an overseas company called Agrimaster and it is also the name of a model of tractor, so there are plenty of people using the hashtag who are definitely not agreeing to the terms supplied by the Australian software company.