A New York judge has ruled that embedding an Instagram post on a third-party website is not copyright infringement, as the photographer has agreed to Terms and Conditions that provides the social media giant a sub-licence for all content.

The groundbreaking ruling against the photographer is a stern reminder of how ambiguous and indecipherable T&Cs can be manipulated, and the power and control social media companies hold over photographers and content creators.

The groundbreaking ruling against the photographer is a stern reminder of how ambiguous and indecipherable T&Cs can be manipulated, and the power and control social media companies hold over photographers and content creators.

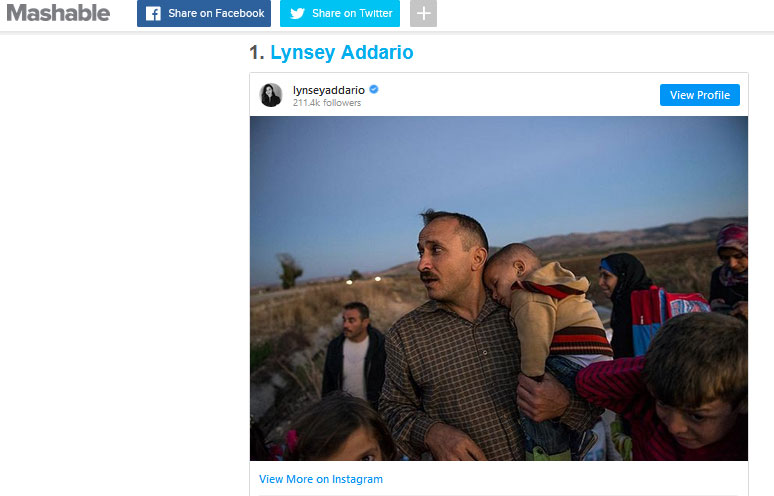

In 2016, photojournalist Stephanie Sinclair sued tech news website, Mashable, for copyright infringement after her Instagram post was embedded in an listicle (remember those?!) titled, ‘10 female photojournalists with their lenses on social justice‘. Mashable initially offered Sinclair a meagre US$50 licensing fee for a photo, and after she declined they found a loophole by embedding the photo directly from Instagram.

Embedding is a feature on Instagram – and other social media platforms like Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Vimeo – which allows third parties to copy code to generate a user’s post on a website. On Instagram the embed feature is available on all public posts, and the only way to disable it is by setting an account to private. For professional photographers, this isn’t ideal as the point of being on Instagram is to promote their work to a wide audience.

Previously in US copyright law, these legal disputes usually revolve around a Server Test. The argument is that embedding cannot be considered copyright infringement, as the alleged copyrighted material is hosted elsewhere – not directly on the defendant’s website server. In this case, the content is hosted on Instagram’s server, and Mashable doesn’t hold an actual copy of the image.

The Server Test has been compelling enough for many US courts to determine embedding doesn’t qualify as direct distribution or publishing, but there are inconsistencies. In 2018 a New York judge ruled that several news sites had infringed copyright when they embedded a photo, setting shaky precedent for future use of the Server Test doctrine. So Mashable’s lawyers reasoned the odds were stacked against them, and instead dived deep into Instagram’s T&Cs and found a sub-licence clause Sinclair ‘agreed to’ when she signed up.

Judge Kimba Wood noted that users provide Instagram a ‘non-exclusive, fully paid and royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license to the Content that you post’.

This clause is fairly standard issue for social media platforms and other online services. While it reads similar to a rights-grab clause the purpose is ostensibly to allow the platform to run smoothly, host user content, and protect itself from potential legal disputes. For instance, the Instagram user experience would be poor if a user had to provide consent for every post. While most users never actually read website T&Cs, chances are these kind of clauses are in there somewhere.

However, Mashable‘s lawyers managed to convince the judge that this clause, combined with the embed feature, created a binding agreement between Sinclair, Instagram and Mashable. It seems unlikely this was Instagram’s intention for the clause, but Judge Wood was persuaded.

‘Thus, because [Sinclair] uploaded the Photograph to Instagram and designated it as “public,” she agreed to allow Mashable, as Instagram’s sublicensee, to embed the Photograph in its website,’ she said.

It’s a kind-of weird scenario, given there is no real interaction between Sinclair, Instagram, and Mashable, and Instagram doesn’t appear to have an interest in sublicensing content to Mashable. But it’s all there, inferred in the T&Cs, it seems. Sinclair attempted to counter the argument by stating the Instagram T&Cs are too complex – they are ‘circular’, ‘incomprehensible’, and ‘contradictory’.

‘[Sinclair] claims it is contradictory for Instagram to simultaneously demand that users respect the intellectual property rights of others when uploading content to Instagram, while also granting those users a right to share other users’ public posts containing copyrighted material. [Sinclair] misses the distinction between a user’s initial uploading of content to Instagram, and a user’s subsequent sharing of content that has already been uploaded to Instagram,’ Judge Wood said.

Sinclair’s final point is that Instagram places professional photographers between a rock and a hard place – either set a profile to Private and limit the exposure on ‘the most popular public photo sharing platform in the world’, or stick to Public and grant all of Instagram’s ‘sublicencees’ unfettered access to free content. The judge agrees this is a ‘dilemma’, but the court ain’t going to release her from Instagram’s shackles.

It’s an unfortunate ruling for photographers, as this paves the way for media companies and other businesses to sidestep a direct licensing agreement so long as the photo is on Instagram. The onus is on a media company to recognise the value of a photo.

PhotoShelter’s CEO, Allen Murayabashi, is suggesting Instagram make a ‘simple fix’ by allowing users to check a box regarding embedding preference. In his vision, this would allow a media company to still embed the post, but it would blur the image and ask viewers to click on a link to directly visit the post on Instagram.

‘… Consider the legal fees that Sinclair has accrued fighting Mashable, and consider an entire class of worker that will be adversely affected by Judge Wood’s ruling. The economic impact is non-trivial, and I would argue that the fix is so easy and would have so little impact on Instagram’s bottom line that they have a moral responsibility to act,’ he wrote.

Yep, it would be a simple fix. But since when does Instagram care that much about its users?

Be First to Comment