Wesley Stacey died Bega Hospital 9 February 2023. My first meeting with photographer Wesley Stacey was at his Annandale home in Sydney 1974, writes esteemed photography curator and historian, Gael Newton. He was already well known and recognised as one of the most tuned-in figures of the new art photography scene.

I was an aspiring young photo curator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Wesley was a founding member of the Australian Centre for Photography.

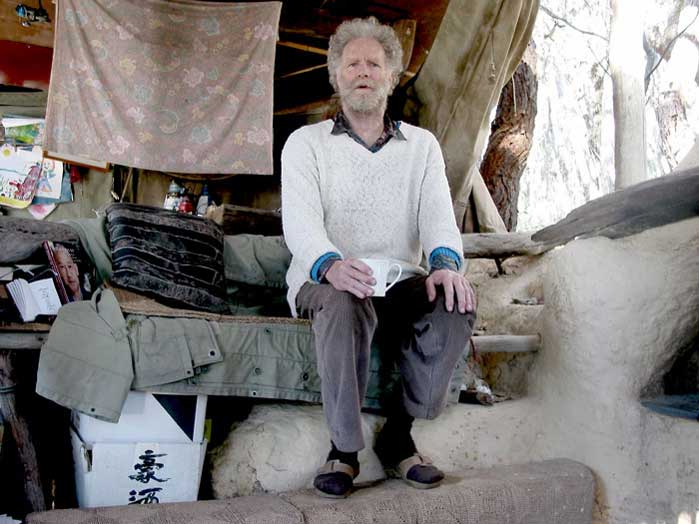

I see him as he was then a lanky lean body with a big head of curly hair and a personality bubbling with enthusiasm for photography and life. That body shape and hair as well as his passion and a certain wry, good humour remained constant throughout Stacey’s career involving quite a few evolutions over the next two decades.

I relocated to a position at the National Gallery of Australia in 1985. By that time Stacey had long since taken to life on the road in campervan from 1976 with partner Ellie Williams, and would eventually work for decades to come out of a base camp at Bermagui with later partner Narelle Perroux. While they were still partners, Wesley and Narelle were regular visitors to my home in Canberra.

Trained as a graphic designer, Stacey had transitioned to a new vocation as a roving magazine photographer by the late 1960s. By 1974 he had signalled his embrace of the counter-culture zeitgest’s liberality with a book on Kings Cross with Melbourne photographer Rennie Ellis in 1970.

At the same time in association with architect Philip Cox, Stacey published Rude Timber Buildings of Australia in 1969 with classic beautiful moody in black and white landscapes and rural vernacular buildings. His magnus opus Timeless Gardens was published in 1977 with Eleanor Williams.

Stacey’s now rare photo books are landmarks of changing social attitudes in Australia – he was saluted as ‘a living legend of environmental photography’ by curator Stephen Zagala on the occasion of the Monash Gallery of Art’s Stacey retrospective in 2017.

Like 19th century American poet Walt Whitman, who embraced his own contradiction and proclaimed he could ‘contained multitudes’, Stacey moved easily between different bodies and formats of work. He seized on new non-professional Instamatics and Polaroids in the early 1970s, whose colour and speed allowed for the immediacy the brand name promised.

His sequences shot from car windows put a wild new spin on the American road trip photography. In 1975 came The Road, 280 snap-shot size prints arranged in panoramic geographic sequences. I viewed it just after installation at the Australian Centre for Photography with David Moore – we were both awed in recognising how the work was an Australia we knew.

Moore had initiated the proposal for an Australian Centre for Photography in the early 70s. Stacey was the representative of the young generation collaborator he recruited at the outset as campaigner and board member.

Wonderful panoramic landscapes in the 1980s saw Stacey cross the continent, and take the form of magical black and white and colour portfolios.

A remarkably intense and prolific photographer until his later years, Wesley Stacey’s legacy is held in libraries and museums but the full measure of his vision and exemplary practise is yet to be fully appreciated.

His stream of consciousness, his ‘artist statement‘, for the 1988 ‘Living in the Seventies’ exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia captures his passion. Here is the artist statement:

Using the outer light, return to insight.’ Lao Tse (China, 6th century BC)

Is photographing the landscape merely a vain attempt at souveniring something from the place?

Is it a familiarizing process, an act in comprehension of the environment?

Is it an act of superiority, trying to tame these wondrous surroundings? Could it be that we like to arrest life with photography, and in capturing a bit of the cosmos get temporary satisfaction of power over decay.

What about landscape as purely an arrangement of forms to delight the eye, the materials of artistry, for the artist’s aesthetic imagination?

Or more importantly is that familiarizing process the beginnings of a deeper understanding of where our place is in the relation of things? A coming to terms with the place? Even a celebration? Perhaps the spirit of the land is calling one to respond.

I study the subject of landscape picture making, the traditions, the visions, the heroes – and continue to have a go at making some for myself, oft wondering whence comes the drive to keep at it – and the function landscape pictures have in our culture.

I allow myself to be drawn to landscapes and sometimes I feel like Luke Skywalker, with an accompanying life-support vehicle, on the Desert Barrier Range, remote.

I love being out in it, immersed, involved with photographic possibilities, with my individual point of view, personal but shareable – essentially interactive with others.

The interacting elements of this place – me here – this time could be made explicit in some photography here. Cloud shadows are racing across grassy hillsides. The light is looking great.

Here is a subject I now have a fix on, or it has a fix on me, and the light is changing quickly. It might not be so good in a minute. This is a scene the landscape photographer must rise to. It will add to the landscape genre.

What this picture probably won’t show is the urgency and compulsion I feel now this potential photograph has become important to me. How quickly can I get the camera in position?

The ancient wisdom comes to mind: ‘He who acts defeats his own purpose’.

But still calculating the permutations and the circumstances I’m on the run, with the elements in a state of flux.

Self-esteem demanding: For the picture! For the glory! (Ego-computer records motive: vanity/whim).

I’m going for it. This is photography. Astride the wire avoiding the barbs.

Where exactly to place the camera?

Forward back check framing

secure tripod up down calm down

be here filter on? Calm speediness.

Speed aperture don’t forget focus!

This place me here this time.

Light’s gone flow with the go.

Light’s come good check framing

press shutter release no click!

Keep calm, logic will solve this.

Cock the lens – Ferglewit!

Light’s good – Fire one!

Wind on replace …

The lens cap is on!Did I replace it automatically without thinking? I think I had it in my hand for the exposure.

Light’s still there. Try another one? No. That’s it. Too bad if its a blank frame.

I’ve turned my back on it and now what’s important is to be here, responses open, and perhaps something will come of the experience.

Buffeting wind, stubble and rocky ground. Light rain prickling furrowed brow.

Tripod and camera askance over my shoulder.

Maybe I could enjoy the place more without trying to take a photograph. Although doing this sort of thing gives me continuity and some sense of purpose. In some ways it satisfies.

Especially if an exciting picture comes of it. Can’t wait to process the film and see that image.

That’s something to look forward to.

The most exciting pictures are still in the camera.

Tantalizing.

Wesley Stacey

Autumn 1988

This tribute was written by Gael Newton, and originally published here. More of her writings about Wesley Stacey, including a large selection of his photos, can be found here.

MGA’s curator Stephen Zagala talking on Wesley Stacey from Monash Gallery of Art on Vimeo.

Be First to Comment