US professional photographer, Lynn Goldsmith, has won her enormous six-year copyright court case against the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF), setting a clear new precedent about Fair Use that will benefit fellow photographers and creators.

It’s the second copyright victory for US photographers in a matter of weeks against two famous (notorious?) art appropriators, Andy Warhol and Richard Prince, with the Fair Use exception to infringement being thoroughly tested by the courts.

While Goldsmith’s lengthy court battle now comes to a close, fellow US professional photographers, Donald Graham and Eric McNatt, are just getting started with proceedings against Richard Prince, with a judge dissatisfied with Prince’s submission to have the lawsuits thrown out pre-trial.

It’s even possible that Goldsmith’s legal victory has set a precedent that will be used against Richard Prince. Click here for the Richard Prince article.

Background

The AWF sensationally sued Goldsmith pre-emptively in 2017, after the photographer alerted the Foundation to the copyright infringement following the musician’s death.

She captured Prince’s portrait in 1981 while on assignment for Newsweek. And in 1984, Vanity Fair paid US$400 and artist credit for a one-off licence for ‘an artist’ to create an illustration, failing to mention the artist was Warhol.

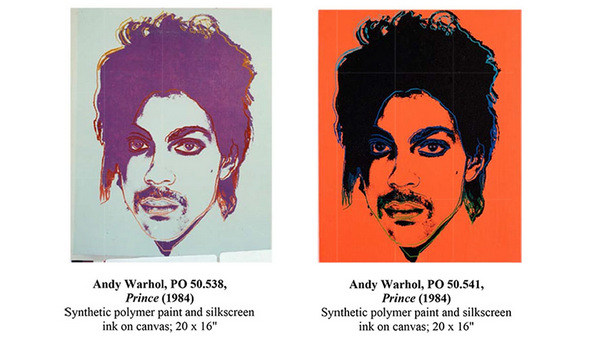

Images of Prince flooded social media in 2016 following his death, and this is when Goldsmith discovered that Warhol created 16 screenprints based on her picture. Crucially, in the final ruling Vanity Fair‘s parent company, Condé Nast, published a special issue celebrating Prince’s life, paying the AWF US$10,250 to licence one of Warhol’s Prince prints.

The pre-emptive lawsuit by AWF was an attempt to prove Warhol’s work was Fair Use, which is determined by four factors, the most frequently utilised being whether the work was ‘transformative’. But also, and ultimately of great significance, the nature of the work’s usage.

AWF initially offered Goldsmith US$15,000 to settle, the photographer told Women’s Wear Daily (WWD), vowing to otherwise take the trial all the way up to the Supreme Court in a lengthy and expensive legal battle.

In the initial lawsuit, AWF went hard on the ‘transformative’ argument, highlighting how Warhol’s print differs because it flattens the subject’s appearance; crops solely on Prince’s face; unnatural colours; Prince’s hair is a solid block and not ‘strands of hair’.

In 2019 the courts ruled that Warhol’s work was Fair Use, which Goldsmith appealed. And won. Here’s an excerpt of Inside Imaging‘s coverage:

‘In her appeal, Goldsmith firstly argued that the perceived intent of the artist – her photo making Prince look ‘not comfortable’, and Warhol turning him ‘larger than life’ – cannot constitute a transformation. Over time, an audience’s perception of the art piece may evolve, making the artist’s original intent redundant. The Appeals Court agreed.

‘In conducting this inquiry, however, the district judge should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue,’ the court ruled. ‘That is so both because judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective.’

Goldsmith also argued that just because it’s recognisable as a Warhol work, doesn’t provide the renowned artist the privilege to copyright infringement. Again, the court agreed stating that the transformation must comprise of ‘something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work’.

The AWF, true to their word, submitted an appeal to the Supreme Court, with the decision going to a 7-2 vote in favour of Goldsmith from Supreme Court justices.

The ruling hinged on the fact that both original works involved a commercial magazine licence agreement. Essentially, Warhol’s work was competing with Goldsmith’s original.

‘To hold otherwise would potentially authorise a range of commercial copying of photographs, to be used for purposes that are substantially the same as those of the originals,’ wrote Justice Sotomayor, on behalf of the majority, about their decision. ‘As long as the user somehow portrays the subject of the photograph differently, he could make modest alterations to the original, sell it to an outlet to accompany a story about the subject, and claim transformative use.’

The two Supreme Court justice voting parties – the majority and minority – then indulged in some exciting verbal jousting over the ruling. Sotomayor describes the dissenting camp as basing statements on ‘a series of misstatements and exaggerations, from the dissent’s very first sentence to its very last.’

Justice Kagan, representing the outvoted judges, responded ‘the majority does not see it. And I mean that literally’.

‘There is precious little evidence in today’s opinion that the majority has actually looked at these images, much less that it has engaged with expert views of their aesthetics and meaning,’ Kagan said.

‘Suppose you were the editor of Vanity Fair or Condé Nast, publishing an article about Prince. You need, of course, some kind of picture. An employee comes to you with two options: the Goldsmith photo, the Warhol portrait. Would you say that you don’t really care? That the employee is free to flip a coin? In the majority’s view, you apparently would.’

She added: ‘All I can say is that it’s a good thing the majority isn’t in the magazine business. Of course you would care!’

Sotomayor, firing back, reminds Kagan that their interpretation of Fair Use doesn’t permit competitive usage.

‘All of Warhol’s artistry and social commentary is negated by one thing: Warhol licensed his portrait to a magazine, and Goldsmith sometimes licensed her photos to magazines too,’ she wrote. ‘That is the sum and substance of the majority opinion.’

Sotomayor acknowledges that ‘photographers like Goldsmith make a living’ by licensing photos to be used in derivatives. ‘They provide an economic incentive to create original works, which is the goal of copyright.’

Goldsmith reflecting on the win

Goldsmith, 75, wasn’t confident about winning the case. She feels Fair Use primarily benefits ‘deep-pocketed corporations, foundations or individuals’, such as Warhol/AWF and Richard Prince. In total the legal fees were US$2 million. Goldsmith believes the AWF underestimated her fighting spirit.

‘I’m about breaking limits,’ she told WWD. ‘I would bet that the Warhol foundation thought I would fold. They [probably] thought, ‘Oh, she’s just some little rock-‘n’-roll photographer’. They didn’t know I’m from inner city Detroit — not the suburbs — and you had to stand up and fight for yourself.’

While receiving an endless stream of goodwill from the arts community, Goldsmith is hurt by the lack of financial support. A GoFundMe crowdfunding campaign to help pay the legal bills and ‘define what is transformative under the Fair Use aspect of the copyright law’ garnered US$58,923, falling short of the US$450K target.

‘It’s pretty sad. It made me an angry, hateful person. I used to really love artists, she said. ‘My thing is if you don’t stand up for your rights, you lose them.

‘There were incredibly successful celebrity portraiture photographers that I know who have had the same thing happen to them all the time, who said they supported me. It’s not like you are a student trying to pay your rent.’

Be First to Comment