The tenth Ballarat International Foto Biennale (BIFB) has concluded its two month city takeover, offering an unbeatable format that provides attendees a great reason to visit the historic Victorian city.

And to be clear, there are not many reasons to visit Ballarat on the edge of winter. This time of year Victorians are either in hibernation, making a pilgrimage north to warmer pastures, or spending a fortune on an European summer holiday. Ballarat – a city seemingly plagued with a cold, wet and windy microclimate – is no winter wonderland. Yet once every two years BIFB presents a great excuse for a voyage, whether that’s a day trip or a weekend. Or something even bigger.

BIFB’s new CEO, Vanessa Gerrans, informs Inside Imaging visitors and volunteers travelled from interstate for the exhibition. Some even boarded long haul flights across the Pacific – coming from as far as Peru specifically to attend the festival.

Right place, wrong time: Outdoor installations

So Inside Imaging‘s team of two made the 90 minute journey up the Midland highway. And, yes, the rain was relentless. Perfect conditions to spend a day inside galleries. Not a great day for checking out the outdoor installations. The images are similar to ‘paste ups’, where they’re printed onto poster paper and glued to a building’s exterior. It’s an art form popularised by music promoters to advertise events and street artists. The quality of BIFB’s outdoor display work was at a much higher quality.

By adorning a building’s exterior with photography, BIFB is beautifying the city and providing passing foot traffic something interesting to look at. By expanding away from the indoor venues where only ‘the converted’ wander, and placing photography in front of a broader audience, the festival becomes more of a general community event.

View this post on Instagram

Kate Ballis’ installation of infared photography, Portals To Atlantis, at the Ballarat Train Station added a welcome splash of character to a building that’s sole purpose is to provide travellers a functional place to wait in transit. William Yang’s single image in a window at the Chinese Library on Lydiard Street fell short of what I initially expected to be a full exhibition. Stumbling upon Oculi photographers’ work in outdoor locations around Ballarat’s city centre was a pleasant surprise, but they’d be elevated to another level on centre stage at an indoor gallery.

For some attendees these installations may be their favourite component of the festival. I reckon it’s an ordinary medium for viewing photography – broader exposure notwithstanding.

Our attendance was late in the festival’s two-month lifespan. It’s a looong time for a large arts event to run. In previous years there were rumours that volunteers’ interest waned towards the end, and there was a risk of exhausting this valuable resource. But signs of a slowing momentum – tired and empty exhibition spaces and weary attendants – were not apparent. The volunteers were plentiful and chirpy, and groups of high school students and elderly people swarmed through various Lydiard Street venues. Every exhibition attended, from paid ticket venues to crumbed chicken franchise, Schnitz, had BIFB visitors on this rainy week day.

The Art Gallery of Ballarat, showing numerous Core Program exhibitions including the headline retrospective by Platon, was the first stop.

Effacement, a collaboration between Ballarat locals, photographer Karenne Ann and crochet artist Heather Horrocks, occupied the first gallery space. Horrocks has been crocheting for around 70 years, and when Covid reared its ugly head she began experimenting with extremely fragile video tape to make a series of woven shiny black masks.

Next up was The Stephanie Collection by New Zealand portrait photographer Yvonne Todd, which on first glance look like a series of conventional fashion photos straight from a glossy beauty magazine. Upon closer inspection, each portrait looked not quite right. They had an eerie demeanour and it wasn’t quite clear how to read them. It was re-assuring to double back to the exhibition description explaining the ‘unsettling’ nature of the portraiture is, in fact, intentional.

Instant Warhol is a series of original Polaroid portrait snap shots by the pioneer of pop art. The prints show Warhol’s friends and colleagues, mostly celebrities, snapped indoors or at night with full flash. The tiny instant prints covered the walls ‘Salon style’, with captions on an adjacent wall prompting a double take to identify the subject.

It’s intriguing to see famous faces in a relaxed environment, shot by a glorified snapshooter with an ordinary camera. Many people likely have their own small collection of instant prints that aren’t too far removed. The glaring difference being Warhol’s exclusive access to celebrity, and the eccentric art crowd he ran with. Gerrans noted that Instant Warhol was a big hit with secondary school students – no surprise given the revival of instant film photography.

The headliner: People Power – Platon

The headline exhibition, People Power – Platon, is a crowd-pleasing world premiere consisting of 139 prints by US-based celebrity portrait photographer, Platon. Working for the likes of The New Yorker, The New York Times, Time, and Vanity Fair has provided Platon unfettered access to celebrities and world leaders.

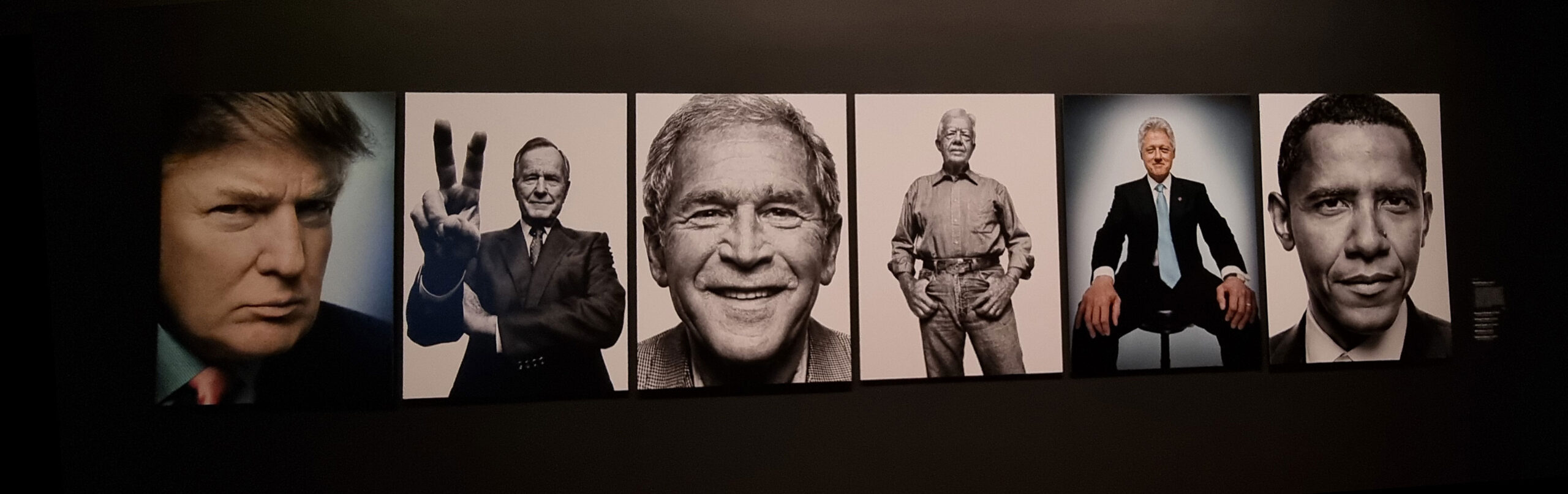

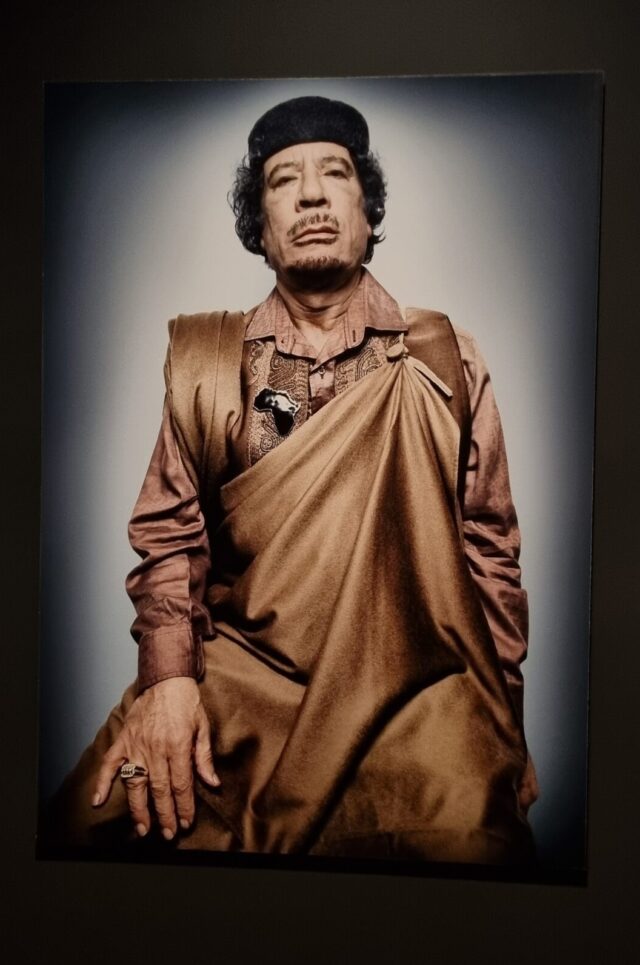

Visitors are first greeted by US presidents. A frowning Donald Trump; George HW Bush throwing a peace sign; his son, George W. Bush, sporting a goofy grin; and Barrack Obama carefully holding a steely gaze. Starring back at the US presidents are enemies of their Western and democratic value systems: Vladimir Putin, Muammar Gaddafi, Robert Mugabe, Hugo Chavez. Hats off to Platon for getting these stubborn bastards into the same room together!

The next space houses the celebrities. Despite most portraits utilising the same format – black-and-white with a plain back drop – each is unique. Even if it’s the first time viewing them, the portraits feel familiar. This might be because the subjects are household names, and the concept or idea that we collectively attach to the celebrity filters through.

The remaining rooms show Platon’s activist work through his non-profit, The People’s Portfolio. It combines documentary photography and Platon’s signature portraiture style with the aim to ‘tell the story of emerging human rights defenders and the people they serve and help them develop a leadership platform’. It’s a welcome addition to the exhibition, which may have otherwise been somewhat one dimensional. Two emotional elderly ladies viewing the Sexual Violence in Congo were blown away, and had to take a few moments to sit down and take in this image:

A friend accompanying me on the trip noted how some of Platon’s image captions included full details, while others had no information beyond the title. As a curatorial assistant, he found it unorthodox and kind of off-putting. ‘It probably doesn’t bother most people,’ he said, ‘but I’ve never seen it done like that’. A gallery staff member he ambushed wasn’t 100 percent certain why, but suggested Platon’s dyslexia may play a role. Platon has stated his reading difficulty means he ‘can’t really function with a lot of complicated things on a page’. (BIFB confirmed this played a role in the disjointed approach to captions)

Further along Lydiard Street is the Post Office Gallery, where photojournalist Stephen Duponts’ Fucked Up Fotos was on display. These pictures are linked by failure, leaving them useless from a documentary photography point of view.

Here’s an excerpt from an essay by Dupont for his photo book of the same name:

‘It’s the imperfections in photographs that makes them unique; beautiful; makes them great. Perfection is boring. I think it was Salvador Dali who once said, have no fear of perfection because you’ll never reach it. Fucked Up Fotos takes my philosophy of imperfections to a whole other level. There is very little of me in these photographs. In fact, the images were not exactly made by me at all. Of course I created them, but who really made them what they are? Science? Nature? My own negligence? Outside interference? These photographs, once dismissed as poor rejects, are sometimes extraordinary, magical and poetic. They’re destructive and layered moments; complex and mysterious, like a painting they invite us to look much deeper, revealing interwoven fragments of time and space. In the end they offer new meaning to the art of photography itself, like fractured puzzle pieces from a waking dream.’

Here’s a slightly related side note. The late and great war photographer, Tim Page, mentioned to Inside Imaging in 2021 that Dupont’s open-mindedness to imperfection made him a thoroughly enjoyable co-worker when editing a comprehensive retrospective of his Vietnam photos. Page, a mentor and close friend of Dupont who is a portrait subject in Fucked Up Fotos, found new meaning in his work’s imperfections thanks to Dupont’s philosophy.

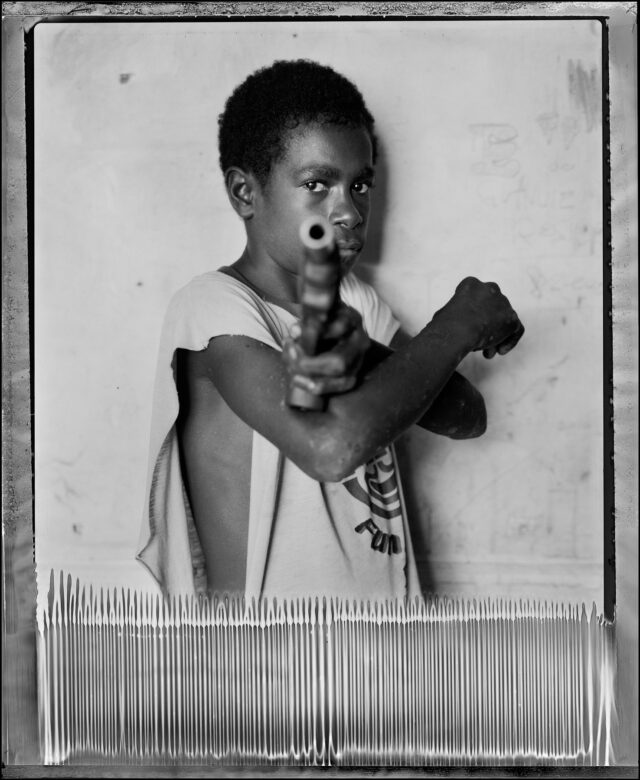

Fucked Up Fotos has two standout images.

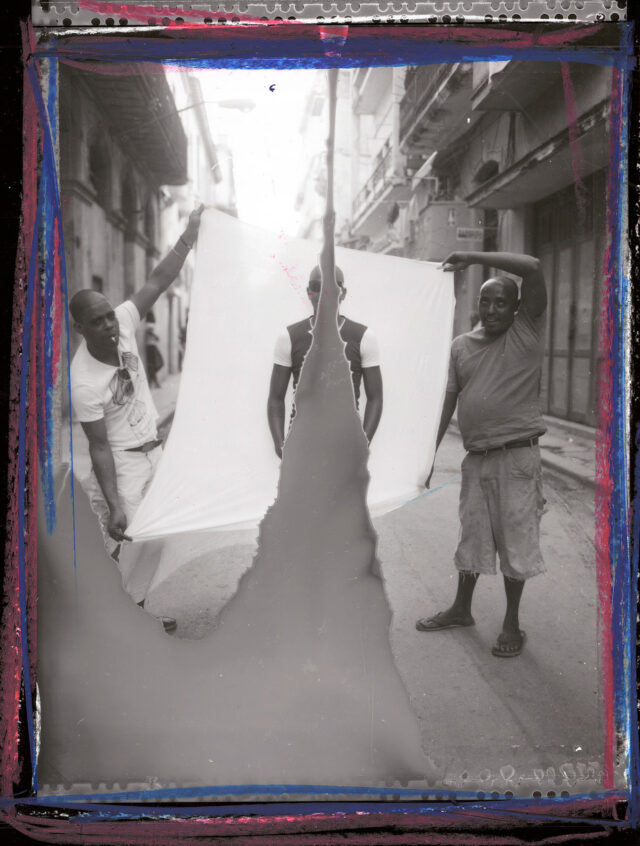

The first shows a young boy from Port Moresby, part of a criminal ‘Raskol’ gang, aiming a pistol at the camera. A dark room editing error left the bottom of the frame stripped apart like threads, by sheer co-incidence resembling the boy’s tattered white singlet. The other is part of the White Sheet series, where a bed sheet is used as an impromptu portrait back drop. An editing mistake resulted in the frame appearing ripped down the middle through the portrait subject, making it look as if the men holding the sheet are in some way responsible for either ripping or holding the picture together.

The Mining Exchange hosted a large exhibition of large prints, How To Fly, by Swedish digital photo artist, Erik Johansson. This exhibition was a highlight in terms of the presentation, with the prints suspended from the ceiling, excellent lighting, and flawless printing quality. Johannson is a master illusionist and digital manipulator, whose uses photo elements to create composites that are surreal yet retain enough realism to fool the mind. Some images are subtle with few fantastic elements. A kind of psychedelic dreamscape, tricking the mind into filling the gaps and interpreting an image as normal, before de-coding the surreal elements.

Other concepts are more outlandish, resembling a fairy tale scene which doesn’t trick the mind so much. My colleague described them as ‘whimsical’. It brought to mind kooky movies from my Millennial youth, like Big Fish, Pan’s Labyrinth, or The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus. Johansson has unlocked the secrets of blending light and layers. His process is carefully executed. Only eight new pictures are made each year. His TED talk is worth watching for more context. While this style of surreal photo realism is not my cup of tea, Johansson is clearly a master. It’s no surprise to find out he worked with an architect on the exhibition design, and most likely oversaw the printing. The presentation is an exercise in how a style of work that’s not necessarily to an individual’s taste can still make a lasting impact.

A triumphant debut

BIFB’s tenth run is the debut festival for Gerrans, who succeeded Fiona Sweet in 2022. Upon taking the reigns she didn’t play around with the format. What she did do is surround herself with a team who are deeply immersed in photography. It showed. There was a variety of work that displayed what can be done with the medium. Following the festival’s conclusion, Gerrans made this reflection to Inside Imaging:

‘Overall there was a feeling of excitement that is very satisfying to our small team,’ she said. ‘We hoped the yellow bags would be out in force. They certainly were, and we were reminded how unique this festival is to Ballarat. People loved to intensity of work displayed on and around the main Lydiard Street. This was a fantastic backdrop to visitors sporting their yellow bag and it built a great sense of camaraderie.

‘This festival is regional at its heart – from ideas forged in Ballarat by locals, and cultural industry workers and community members understanding the economic benefit it brings to the City. Ballarat residents have clearly honed an awareness and understanding of photography over 10 iterations of exposure to the photography medium through this festival that I found inspiring.’

More photography was on show that’s equally worthy of mention, but beyond the scope of this piece. In total we clocked about 20 exhibitions in a day visit, with a brief lunch intermission to find the most throwback country town Chinese restaurant possible. It’s a great day out. A whole weekend, preferably on opening weekend to experience the full buzz of activity, would be ideal.

But nevertheless, BIFB’s tenth run is a testament to Ballarat’s strong commitment to celebrating photography through an unbeatable festival format.

Be First to Comment