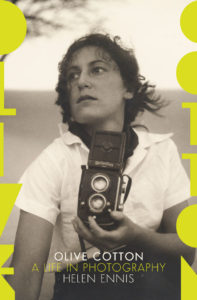

Olive Cotton: A Life In Photography, an in-depth biography tracing the story of the groundbreaking Australian modernist photographer, may be the biggest project undertaken by author Helen Ennis.

Helen, former curator of photography at National Gallery of Australia (1985-1992), did her legwork to piece together Olive’s story in the 544-page novel. She spent eight years slowly researching and interviewing people who knew Olive.

‘It’s the ordinary and extraordinary that I’ve tried to weave together, because her (Olive’s) achievements, when confined to the professional realm are amazing, but I think that what we know from biography is the interest and also in how people choose to live their lives, not just these big achievements,’ Helen said to the Cowra Guardian. ‘So it is a long book and that’s important, to make a woman’s life the subject of such extended research and such focused attention, but also to be able to have ordinariness in there, anecdote and recollection.’

The following is an extract.

The Trunk

At Spring Forest, the property where Olive Cotton lived for over fifty years, there is a large

traveller’s trunk that originally carried her belongings from Sydney to her new home in the country. At one point, it was filled with her photographs, the negatives and prints from the years spent working at the Max Dupain Studio. These days, the trunk sits on the dilapidated back verandah of the ‘old house’, which was Olive and her husband Ross McInerney’s first home. It is part of an odd array of abandoned items: nearby is an old fridge, a kerosene lamp, some broken-down machinery, glass bottles and other bits and pieces. Still structurally sound, the trunk is battered on the outside – some of its waterproof covering is peeling off – but not to the point that any of its contents are endangered. Inside, in no particular order, are notebooks from Olive’s student days, programs for music recitals and concerts she attended in Sydney in the 1930s, sheet music for piano, and an assortment of books: novels, poetry and plays, some of which were gifts or prizes. One has a book plate in it saying ‘Olive Dupain’; another has a handwritten inscription, ‘Love from Daddy’. None of these things made it into the ‘new house’ at Spring Forest, which she and Ross moved into in 1973, and so they were not physically present in her later life. The trunk, in its rundown location, looks unimportant and could easily be overlooked. And yet it is unexpectedly helpful, because it points to the way Olive viewed not only her past, but also her legacy as a photographer.

Olive Cotton didn’t fuss about the future. She wasn’t one of those photographers who self-consciously assemble and arrange their photographic material, business and personal papers and memorabilia with posterity in mind. She was not at all anxious about controlling her own life narrative and the readings of her photographs. Certainly, she kept things that were important to her – the contents of the trunk are proof of that – and she ensured that her most valued photographs went into public collections in art museums and libraries around the country. This was a process that started in earnest in the mid-1980s, when her work from four and five decades earlier began to reappear in exhibitions and publications. However, her personal archive, housed in the trunk and numerous cardboard boxes stored inside her home, is informal at best, reflecting an attitude to the past that was benign, verging on the fatalistic. So far as we know, she didn’t embark on any dramatic editing or purging, even though there was ample time to annotate or destroy material if she had wanted to – the most intimate being a long letter from photographer Max Dupain, whom she married in 1939 and left two years later, and correspondence with farmer Ross McInerney, her husband of nearly sixty years. Olive chose not to intervene and instead left her past open to the future – any kind of future – free of her dictates and demands.

This position wasn’t simply the result of her view on the value of her work and its legacy; it also related to her understanding of time as being beyond human consciousness and experience. As the daughter of a geologist, she was at ease with notions of geological time and its impersonality, and with what others might see as the wearing physical effects of the natural elements. The state of Olive’s informal archive at Spring Forest suggests that she could accept the deterioration and eventual obliteration of belongings she was once attached to and associated with.

There are pockets of intense fascination in the archive, but it is limited as a potential source of information and illumination, frustrating the biographical process. So few of the items either speak of, or to, Olive’s inner life. The letters from Max and Ross are revealing, although they say more about each of them than they do about her; she flickers in and out of their writing as the one being addressed but never assumes a firm presence. There are no diaries, only a small number of personal papers and some letters, mostly those she sent to Ross during the war and extended periods in the late 1940s and early 1950s when they were apart. As a biographical subject then, Olive has surprisingly little weight. This is compounded by the kind of person she was – her character, her personality, her disposition. A long-term friend, Ernest Hyde, described her as ‘a background figure’, which accords with my own view, gained from a professional relationship that began in 1985, when I was Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Australia, and which later became a friendship. Reminiscences and anecdotal evidence from other people have reinforced this assessment: her reserve, reticence and modesty were commented on frequently, as was her goodness and kindness. Ross told me, proudly, that in their six decades together, he never heard her speak ill of anyone, not once.

During her long career, which spanned two intense phases, from 1934 to 1946, and from 1964 until the early 1990s, Olive never sought the limelight and was not interested in consolidating or extending her influence and reputation. When she spoke about photography publicly, it was only ever her own; she did not comment on the work of others or address the state of photography more generally. On the few occasions she entered into commentary on her work – in oral histories (two of which are in the National Library of Australia’s collection), and in publications – it was invariably due to the initiative of others. While she was delighted by the attention she eventually received, and respectful of it, she was, I suspect, slightly bemused by the fuss.

There may not be a large volume of personal documentation, but there are, of course, her photographs – the very reason for this biography. Olive Cotton is recognised as one of Australia’s most important photographers of the modern period. She created a highly original body of work – landscapes, flower studies, portraits and still lifes – that related to contemporary developments, nationally and internationally, in modernism and modernist photography. Her experimentation with light and its effects, with composition and vantage point, extended the vocabulary of modernism in Australian art to encompass gentler, less heroic modes of expression. Today, her photographs still stand out for their beauty and serenity, and often for their sensuousness as well. In their own quiet way, they have enlarged our sense of the capacity of art photography to move its viewers.

This biography deals with the specifics of Olive’s life and photographic work, but her story, like everyone’s, belongs to its own particular historical moment. As a woman whose life spanned nine decades of the 20th century, she was subject to the larger forces and events that defined her times. Born in 1911, three years before the outbreak of the Great War, Olive entered her thirties during the tumult of the Second World War. She studied at university, worked in the photography industry, and for a short time was a high school teacher. She grappled with marriage, divorce, remarriage and motherhood. She experienced gender discrimination in society and culture. She lived in the city and in the country, drew strength from her close family connections and strong enduring friendships with women, coped with personal loss, and dealt creatively with isolation and ageing. Olive also saw the population of Australia grow and its ethnic composition alter, its economic fortunes fluctuate and its geopolitical alliances change as it emerged as a middle power in the global arena. But it wasn’t these big socio-political shifts and associated issues that found their way into her art. Her concerns and preoccupations were far more personal, always oriented inwards, rather than outwards. As her sister-in-law, Haidee McInerney, perceptively noted, Olive ‘had another world inside her head’ – a secret, private world that depended on her own highly individual responses to what she saw around her. Max Dupain understood this, too. In a review of her 1985 solo exhibition, he remarked that, although Olive’s style was ‘in some ways … documentary … her personal approach is very evident … her work is filtered through her before it goes on to the paper.’ The emphasis was his.

The dearth of primary material has been only one complicating factor in writing Olive Cotton’s biography. Another stems directly from her two marriages. Max Dupain and Ross McInerney were both domineering, charismatic men whose voices in life were far louder than hers. In death, too, Dupain and McInerney each left substantial, albeit very disparate archives. As a consequence, Olive’s presence in her own life narrative is frequently imperilled, at risk of being swamped, even extinguished, by theirs. Wherever possible, I have quoted her as a way of introducing and asserting her voice, and have drawn on a mix of sources to help build a fuller picture of her: official records, books, exhibition catalogues and other publications, my own observations, and comments and anecdotes recounted by her family, friends and acquaintances alike.

Some aspects of Olive’s life are quite straightforward and can be accounted for easily. A geospatial map is, for example, not at all complicated to draw. She did not travel far during her ninetytwo years, with her movements centring on two main areas: Sydney and its environs, including Newport on the northern beaches, and the area around Koorawatha in central western New South Wales, where the McInerneys’ property, Spring Forest, is located. The furthest point north she went was Coffs Harbour, on the northern New South Wales coast, and the furthest south was Hobart in Tasmania (on a trip as a member of her high school’s basketball team). She never travelled to any other states. The only other place outside New South Wales she visited was Canberra, where she honeymooned with Max Dupain in 1939, and went to every now and then in the last two decades of her life to see exhibitions of her work and members of the McInerney family. She never went overseas and flew only a few times, once in Ross’s brother John’s small plane, an experience she enjoyed. She did not learn to drive until she was in her early fifties and was always a reluctant driver. First Max and then Ross were the ones who did the driving, even on her behalf when she had to be somewhere specific. Olive loved to walk, or to use a verb she favoured, ‘to roam’, an activity she embraced from childhood onwards. With its implication of freedom and possibility of chance discoveries, roaming was enmeshed with the joys that came from repeated visits to the same ground: at Hornsby, where she grew up; at Newport, where her family had a holiday house; and at Spring Forest, where she lived with Ross.

There is an additional, far more unusual, though challenging, biographical resource: the three houses where Olive spent the majority of her life. All are still standing, despite the time that has elapsed: Wirruna, the grand Cotton family home in Hornsby, which she left at the age of twenty-seven to marry, and the two-room weatherboard cottge and the construction workers’ barracks, known as the ‘old’ and ‘new’ houses respectively, where she lived for half a century at Spring Forest. Olive died in 2003, and Ross in 2010, but Spring Forest, which is protected by a voluntary conservation agreement, has remained in her daughter Sally McInerney’s family. In the living room of the new house, Olive’s and Ross’s books are still on the bookshelves near the dining table that looks out to the front yard; in the kitchen, their crockery is in the cupboards and cutlery in the drawers, and in the large pantry, jars of fruit Ross preserved are lined up in rows. Olive’s bedroom still contains her made-up bed, and her clothes are hanging in the wooden wardrobe. In the adjacent room, her piano, which originally belonged to her mother, has pride of place; positioned on the left-hand wall, it is the first thing you see as you open the door. In the bathroom, towels are hanging on a makeshift line over the bath and a cake of soap sits on the side of a washbasin. Many of Ross’s clothes and personal items are still in his bedroom.

In the front yard, in the area between the old and new houses, Ross’s broken-down cars, mainly Austin 1200s and 1800s – seventeen of them, at final count – are parked close to an ancient drycleaner’s van and the remains of a rusted-out Buick that Olive’s father, Leo, gave the couple as a wedding present. Ross’s tools, bits of machinery, wood-heaters and fencing wire lie on the ground in rough groupings, and around the back of the new house, near the chook pen, are more vehicles and farm machinery, several stoves, dozens of plastic plant pots, sections of beehives and other paraphernalia.

Spring Forest is a curiously paradoxical site, simultaneously a biographer’s treasure trove and nightmare. Its chief characteristic is excess, the extraordinary profusion of things proving to be more baffling than revelatory. Indeed, if everything had a sound, the noise would be discordant, deafening, overwhelming. This surfeit is at odds with the refinement of Olive’s photography, her elegant, highly organised and uncluttered compositions, and although it means Olive’s lived environment requires no reimagining or recreating – signs of her and Ross’s life are literally everywhere – the stuff left behind gives very little sense of her.

There are a few exceptions. The piano, for example, which Olive had always hoped to have restored so she could play it again, makes her love of music tangible. But the most confounding detail is relatively inconspicuous. On some of the bedroom doors in the new house, small Dymo labels are attached, each of which bears an initial for a first name and a full surname. These identified some of the barracks’ previous occupants, who were workers involved in the construction of a dam at Carcoar in central western New South Wales. The bedroom housing Olive’s piano was once delegated to ‘N. Boardman’, a man Olive probably never knew and about whom she may not have been curious. In the thirty years she and Ross lived in the new house, they chose not to remove the labels on the doors, not to erase the signs of the past, but to leave them there indefinitely.

***

Olive wasn’t tall, a little over 150 centimetres, and was of slight build; Ross, at more than 180 centimetres, towered over her. Her hair and eyes were brown. People did not describe her as a beauty, but said she was ‘pretty’ and remarked on the qualities of her smile, her eyes – their liveliness in particular – and her voice, which everyone agreed was beautifully modulated. In early adulthood, she dressed fashionably, though not flamboyantly, but she did not pay any special attention to matters of clothing or fashion as she grew older. She wore her wedding ring, and a watch on her left wrist, but rarely any other items of jewellery. She never used much make-up, applying lipstick only when she was going out or expecting visitors. Her hair was thick with a slight wave. When she was a young woman, she grew it long for a while, occasionally tying it up in braids she wrapped round her head, but most of the time, she kept it at shoulder length, parting it on the right-hand side and sometimes using a hairclip to keep it in place. She wore a fringe when she was older. She didn’t colour her hair, which greyed slowly but never completely. She was not glamorous, and she was not vain.

From the outset, Olive struck me as someone who was nonmaterialistic (anti-materialistic is far too aggressive a term to be applied to her life view), who placed little store in external ‘reality’ and whose preoccupations were neither literal nor obvious.

The way Olive Cotton presented herself to the world has been crucial to my conceptualisation of this biography. So has the way she spoke. She chose and enunciated her words carefully, there was never any wasted or extravagant language (I couldn’t imagine her ever swearing), no erraticism or emotional eruptions. She spoke softly and slowly, never rushing to fill the silences between thoughts and sentences or chatting merely for the sake of it.

What I have taken from her presence, manifest in part in her way of speaking, is a sense of the deliberation and purposefulness that underpinned her photography. Olive Cotton had an unwavering belief in the value of a creative life and experienced first-hand the struggles and compromises that can threaten to destabilise or even destroy it. She was determined – ‘quietly determined’, as more than one person told me – to succeed in her photography. This meant not accepting the world of external appearances at face value, and searching instead for underlying relationships between physical and non-physical forces, and for intricate, highly mobile patterns that resulted from the unceasing, complex dance between light and shade. In other words, being alive to the lyrical possibilities of her chosen medium of photography, which, in one of her few public comments, she defined as ‘drawing with light’.

This brings me to another fundamental element that has set the tone of my story of Olive’s life: the qualities of the photographs themselves. Olive Cotton’s style did not change radically over the years. She was consistent in her approach, ever respectful and attentive to her chosen subject matter and to the medium she had joyfully discovered as a child. In her photographs, there is no overelaboration or striving for effect, but there is abundant evidence of her ambition and integrity, of seeking what she regarded as pictorially right and true.

This is an extract from Olive Cotton: A Life in Photography by Helen Ennis, published by HarperCollins Australia and now available in all good bookstores and online.

Be First to Comment