With Australia’s cultural institutions acquiring only the most prestigious photo archives, established photographers heading toward their twilight years may need to consider how to preserve their life’s work.

A portion of many photo archives from the last century would likely have some historical value, and could be usefully housed in a public library, museum or gallery. But acquisitions are reserved for the big names, with the last major announcement in mid-2019, when the State Library of Victoria raised $75k in public donations to acquire the great Bruce Postle archive.

‘But for every Postle, there are two or three more who are being not only ignored, but cast over in terms of historical importance,’ retired commercial photographer, Robert Gray, told Inside Imaging. ‘In the end, it’s the dereliction of duty by the public organisations across Australia. They are ignoring their social history responsibilities, and should be embarrassed about it.

‘You have someone like Roger Garwood in Western Australia – he’s shot fantastic images in the Goldfields, covered the America’s Cup. He did everything – one of the towering figures of photography in Australia, and his pictures should be held. Same with Milton Wordley in South Australia. There are photographers in every city who have been shooting pictures of historical merit for a very long time, who have been left to wither on the vine and it’s a disgrace. I’m not a Garwood or a Wordley, but I decided it’s about time someone did something.

Robert approached several public institutions about 20 years ago to discuss taking more photography into the collections. None of them were interested. ‘They don’t have a budget, and it’s all too hard,’ he said.

Robert was hoping to spark interest in work by his contemporaries, which he considers of greater importance than his own. But the sheer lack of interest left the photographer contemplating the fate of his own four-decade archive. If he didn’t assure its preservation, who will? The archive could easily slip through the cracks and be filed away – or even worse broken up or discarded – like many others.

When Robert retired in the early 2000s it wasn’t a great moment to dive into archiving. Digital photography and image file storage had only just emerged, and there was no industry-wide standard. So Robert waited until 2017, by which stage he was ready to begin the digital archiving project, the Robert Gray Photography Archive.

‘Although I am now of advanced years, I don’t have any mortality problems – I’ve never been sick and it’s unlikely I’m going to fall off the perch any time soon,’ he said. ‘I wasn’t in a hurry with this project because there are these curves that I could see moving.

‘One was the fact that the hardware you need is getting more affordable; and the other is the whole Digital Asset Management equation took ages before it was clearly defined and comprehensive. Those two curves were moving, and I was in no hurry because as they moved, the easier and cheaper the whole thing would be.’

Here’s a brief summary of Robert’s photographic career:

– In 1968 he was a cadet at The Age in Melbourne;

– Moved to the Gold Coast in 1976 to work for a magazine;

– Went abroad for three years, based primarily in Hong Kong, shooting commercial and fashion shows;

– Returned to Melbourne in the early 1980s and established one of the busiest commercial studios with the late, great Ian McKenzie until 1987;

– Headed up to Cairns in 1987 and in 2001 he retired in Brisbane.

Archiving? Start now

Photography curator and historian, Gael Newton, cited the legendary photojournalist, David Moore, as being ‘meticulously organised and a businessman‘.

‘On one visit to his beautiful home and studio at Blues Point, David unerringly pulled out a folder and opened it at almost the exact page to find an image for me. David had shelves of ring binders recording contact sheets as an index. The negatives could be located as a result. His daughter, Lisa, who is a designer, runs his archive including vintage and posthumous printings and reproductions. It’s a big job running any kind of picture library let alone an artist’s legacy.’

Robert is similarly organised, and he’s thankful to have always held onto his job books. There ‘wouldn’t have been a hope in hell’ to digitise his archive if he had lost them.

‘[When running a commercial studio] You’ve got to keep track of everything you do. So the job book produced the job number – that was king. That number follows everything around, from the negative filing, ordering of prints, the calculation of how much film we’d shot, resulting with an invoice.’

The first step to digitising the archive was transferring information from the job book into a spreadsheet to create a digital database. This also requires cross-referencing the job numbers and descriptions with the corresponding film.

The next job is turning the film materials into digital files – Rob estimates the various-sized transparencies and negatives account for more than 20,000 images. For this task he consulted the YouTube armchair experts as to how to efficiently and professionally digitise the archive.

‘In the end, I just ended up giving myself a sort of a verbal uppercut saying, “look stop looking for someone else to provide the answer, the fact is you probably more capable than these people, so solve it”. The fog started to clear then, and I started to think of it as sort of almost like a job, as if someone came to me with this problem.

‘This is what invariably photographers are – problem solvers. The end product is pictures, but what we’re selling in the commercial photography industry is problem-solving. So I sat down and figured it out.’

Elaborating about being ‘problem solvers’, Robert explained: ‘I’ve been brought in a few times just because I could solve a problem, such as a long time ago when approached by a graphic designer working for Victoria Police. They were kinky about the colour of their uniforms, and hadn’t found anybody who could transfer the colour into a brochure on film. It was just a matter of light and exposure, and choosing the right film.’

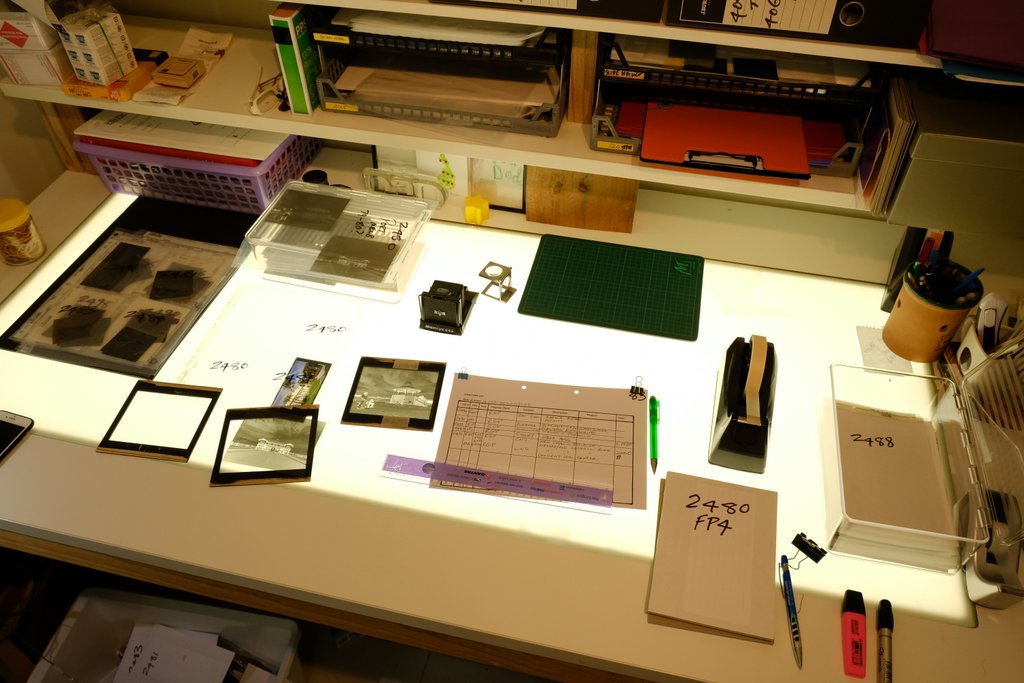

To digitise everything from a 35mm negative to a 4×5 transparency, Rob needed a light table and built two custom camera rigs using a Canon slide copy mount. The camera rig uses a Fujifilm X-H1 with a 60mm macro for 4×5 and 6×12, along with an extension tube for 35mm and 120 film up to 6×9.

The final process is cataloguing the digital collection, and for this Rob sought technical assistance from a student who knows Lightroom. So far there are about 9000 images in the catalogue. The big job here is, of course, deciding what to cull and what to keep.

Rob shot around 15 rolls of 120 film per job, and the rough plan is to retain half a dozen transparencies and four or five black-and-white negatives. His decisions are based on his memory, the image quality, along with the retrospective historical context.

For instance Robert photographed many corporate events in Melbourne during the 1980s for automotive, oil, and shipping companies. Back then there were certain mannerisms, behaviours and a fashion style unique to the place and time. ‘I’m going to edit this back, but keep a hell of a lot. It ceases to be a photographic document, but becomes almost a part of social history.

He continued on that theme: ‘It was a totally different workplace. I shot a car company’s sales conference, and I’ve pulled out the first couple of rolls and look at this picture and I think, “what on earth is that?” The sales conference had, as its final bit of entertainment at the dinner on the last night of the conference, mud wrestling with naked women. That’s an example what you can discover, what you find, that’s unacceptable by today’s standards. So I’ll keep some of that, although there are only about one or two acceptable photos of the mud wrestling.

‘And then there’s just groovy stuff, like aerial shots of the Great Barrier Reef. I have been stunned by the fantastic quality of the film that was around, just before film went away. The film companies, Fuji and Kodak, were producing some of the finest emulsions that could do some of the most marvellous things if handled correctly. And that was the trick, to be able to expose it correctly and your latitudes were very fine.’

While Rob’s aerial photos of the reef were for tourism, the images may serve as a factual record of the reef and be of new interest to the scientific community. Likewise, the images of the mud wrestling reflects a bygone era of male-dominated corporate culture and what was then considered tasteful entertainment for the lads.

These are only a couple of examples of what’s contained within one photographer’s archive. There are thousands more jobs, each with a time, a place, and a story. It boggles the mind about what else is out there, waiting to be discovered.

The Robert Gray Photography Archive is far from completion, with a minimum of three years before it will become available to the public. When ready, Robert will provide a browse-able Excel spreadsheet for any clients interested in searching the database.

– It would be great to think that some of that $6.7 million for the National Centre for Photography could be used for archival acquisitions from the greats of the recent past, and hopefully the current management at Ballarat will grow an interest in this kind-of work!

Rob is being too humble. He brings a unique eye to his work. His archive will provide a great resource for future generations to enjoy & marvel at its depth.

Thanks, Rob Heim….very kind….

Robert Gray