Legendary architecture photographer, John Gollings, is exploring how digital photography has ‘liberated’ the built environment from reality in his latest online exhibition, Truth and Reality.

John has been fascinated with the philosophical issues of truth and reality since he picked up a camera back in the middle of the 20th century. Kicking off his illustrious career as an advertising and fashion photographer, his introduction to the profession was entrenched in selling products, which meant fabricating a reality not beholden to truth.

‘At that time there was a feeling that the advertising guys were the technical gurus, who could create photographs to sell products, and they do that with great lighting, optics, and an imagination,’ he told Inside Imaging. ‘And so when I moved into architectural photography, I brought those advertising skills to the table. I was dropping koala bears and kangaroos into my photos.

‘It was an era of post-modernism, where the theory behind the architecture was quite important, so I was trying to build a narrative within the photo and illustrate the architecture theory. That was very different to the work that, say, Max Dupain was doing through the ’50s and ’60s.’

When Inside Imaging contacted John, he was leaving a job on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula which had been washed out. The house needed late afternoon sun, and the weather was overcast. These conditions wouldn’t necessarily inhibit John’s ability to work – he’s a ‘big believer in cheating with digital photography’ by working some post-processing magic, but the client wasn’t having it and called the shoot off.

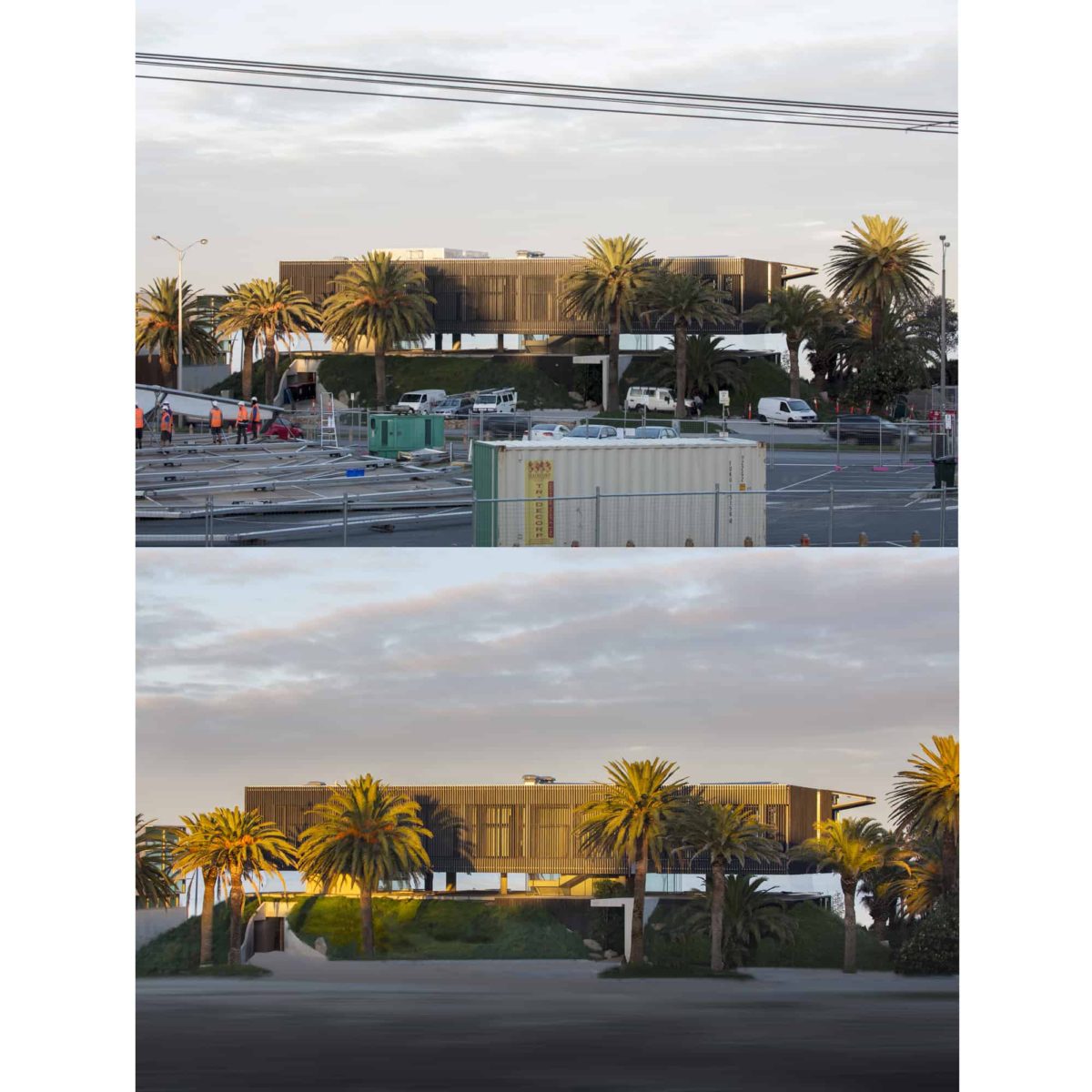

The photos in Truth and Reality are, in many ways, about how John has ‘cheated’ in the pursuit of a more pleasing shot for his clients. Two of the same image are shown side-by-side – the original capture and the final product – to expose how John has manipulated reality.

‘It’s a pretty interesting show, but it’s not art. It’s interesting, I think, more to architecture photographers and architects,’ he said. ‘I’m seriously interested in the philosophical issues of truth and reality. It’s a double edged sword because I’m trying to get more truth by being less real, if that makes sense.’

It didn’t quite.

‘My role as an architecture photographer is to describe a design theory, and how it has been implemented by the architect. So, for example, if a builder is required by regulation to put a big air conditioning duct on a roof, that’s not part of the architect’s design intent. So I don’t feel any compulsion in removing the air conditioner, or the sewerage pipes, or anything that detracts from the clarity. The truth I’m seeking has to be achieved by modifying the photograph – modifying the reality of the architecture.’

The photos in Truth and Reality were primarily shot to publicise the work of an architect to help them gain publicity, win awards and ultimately keep them in business.

John was an early adopter of digital post-processing, but up until 2006 he shot everything on film and generated 100-megapixel digital scans of an image. Before going digital, he masterfully crafted his images in-camera through multiple exposures and proceeded with meticulous work in the dark room. Take his image, Kay Street Housing, a shot from 1982 for the late architect Peter Corrigan. In the foreground kangaroos are gallivanting at night on a busy Carlton street, with Corrigan’s signature work behind them.

At the time Corrigan was beginning to gain international fame and Italian architecture and design magazine, Domus, wanted to publish his work. He sent over a few snapshots that didn’t do the work justice, so Domus suggested he hire a professional photographer.

‘I knew Peter, so he rang me up and asked to grab these shots for the magazine. He wanted something quite theatrical, and at the time I was doing work for Melbourne Zoo and had been shooting kangaroos at nighttime. It struck me that it would be a nice joke to infer to the Italians that kangaroos are all up and down our suburban streets. It’s become, embarrassingly, a bit of an iconic shot of mine and goes way back.

‘I had some very big Durst enlargers, and I was pin registering the kangaroos onto 10×8 film in my colour lab. It was pretty obsessive stuff, and when I could I recreated the shot digitally to improve some of the edges and things. So I’ve been doing this stuff for a long time, and still getting better at it.’

When digital technology became accessible, it liberated John from the darkroom. Around two thirds of the photos in Truth and Reality are captured with a Canon DSLR or Sony mirrorless full-frame camera, and finished on a computer.

‘Now in post production with the RAW file, I usually combine two of three different exposures then start dodging and burning, which is very similar to what you could do in the darkroom with your hands under the enlarger. Then there is the edge burning, the Ansel Adams stuff that contains the eye in the middle of the picture.

‘And then I look at saturation and colour balance, or maybe the photo should be black and white. And I’m fairly obsessive about a pretty strong composition, where the main force lines are the platonic solids. Then there is the retouching, I take out the exit signs and the power lines, and before you know it you’ve spent an hour and completely changed the picture. And it can become a very powerful document.’

No time for ethics in architecture

Nowadays, architectural photography has a rather loose ethical framework. While John’s series has echoes of the 2016 exposé on Steve McCurry’s travel photos, he feels his work is the complete opposite to documentary photography. It’s probably closer to virtual reality and 3D rendering – technology the architecture industry has embraced. John may have had a slight pioneering role to play in that. In the late ’80s, he began placing photo realistic elements of a built structure over an architects CAD file plans to create a visual render.

But it wasn’t always this way. John was mentored by the absolute legends of photography, such as Ezra Stoller, Ansel Adams, Wolfgang Sievers, Mark Strizic, David Moore and Max Dupain. Reflecting on their approach and work, he speculates some would subscribe to ethics that wouldn’t be as laid-back as his approach.

‘I believe this is an issue worth raising for other photographers to think about. Some of the guys in America don’t believe you should alter the building too much – they’ve got a slightly different approach. There’s four different approaches in the show, and I think it’s a fascinating exercise to look at.’

John Gollings’ Truth and Reality is showing online at the Queensland Centre for Photography. Click here to check it out.

Be First to Comment