An attribute common to many photographers featured at the 2018 Head On Photo Festival in Sydney is an implicit push for social or political change. That’s just about where the similarities end.

Attendees will find stories about life, death, and love; living with disease, and through war and peace; cultural practices and identity; global industrialisation, and nature; fashion and body painting; and simple moments and experiences. Humankind at its best and worst. The photos are pretty good, too!

In its eighth year as a festival, the Head On Photo Festival’s roots are firmly planted in Sydney’s cultural landscape.

As one of the largest photo festivals in the southern hemisphere, it’s difficult to imagine how the non-profit Head On Foundation grew from an exhibition in 2004 with a simple mission: to showcase photography based on the merit of the work, not the reputation or profile of the artist.

In 2004, the inaugural Portrait Prize contest used blind judging to select a winner, an approach which continues to this day.

Pictures by emerging photographers appear next to work by established and celebrated artists, and this is a driving force behind what makes Head On unique.

ProCounter attended the Head On opening weekend, and here’s an overview of what’s on offer.

The exhibitions

Paddington in Sydney’s inner-east is the festival hub, and where most exhibitions can be found. Town Hall, an ‘aesthetically pleasing’ Victorian-era building, houses 12 exhibitions alone.

While there’s no headline exhibition at Head On, the Portrait Prize exhibition takes center stage at Town Hall. This is, after all, where it all began.

The portraits vary from studio-style and posed, through to naturally lit reportage photos. Then there’s the downright weird.

Blind judging ensures there’s a level playing field, and a mix of local and international judges prevent any potential bias toward recognisable photos.

Of all the 40 finalist images, only two photos by Australian photographers were familiar due to recent award wins. The Nikon-Walkley winning Lion Heart Leo, by Sam Ruttyn for the Sunday Telegraph; and World Press Photo Contest winning portrait of Aisha, by Adam Ferguson for the New York Times.

The winning image is a simple family moment captured by a Brazilian-based photography couple.

Attendees walking clockwise through the main exhibition space will be first greeted with SCAR, a series of fine art conceptual images by Broome photographer, Michael Jaluru Torres.

SCAR, Michael’s second solo exhibition, features portraits of indigenous Australians with traditional carvings etched into the prints. Most of the photos are black-and-white or have deep colours, with a particular dark ‘pindan’ red dirt shade that’s found throughout the western Kimberley region.

While the photos present the beauty of traditional design and culture, some are inspired by traumatic events faced by indigenous Australians.

During one of the many free Head On artist talks, Michael (right) explained his photo of a pregnant women, with her belly half immersed in a rock pool, is an interpretation of forced pearl diving. When Broome’s famous pearling industry began, some indigenous women were captured, sold, and forced to dive for the shells. It was thought their pregnancy gave them better lung capacity. This dark part of colonial history has only recently became officially recognised.

During one of the many free Head On artist talks, Michael (right) explained his photo of a pregnant women, with her belly half immersed in a rock pool, is an interpretation of forced pearl diving. When Broome’s famous pearling industry began, some indigenous women were captured, sold, and forced to dive for the shells. It was thought their pregnancy gave them better lung capacity. This dark part of colonial history has only recently became officially recognised.

Another photo, a women painted black holding her white-painted daughter, is Michael’s interpretation of the stolen generation. The women in the photo is the granddaughter of Daisy, one of the three mixed-race girls whose story of walking over 2000km to escape the Moore River Native Settlement was turned into the movie, Rabbit Proof Fence.

Walk counter-clockwise through the exhibition space and there’s Afghanistan: Between Hope and Fear, a series by award-winning American freelance photojournalist Paula Bronstein.

Paula’s photos capture the everyday life of Afghan people, particularly women and children, who innocently attempt to lead normal lives despite the backdrop of war.

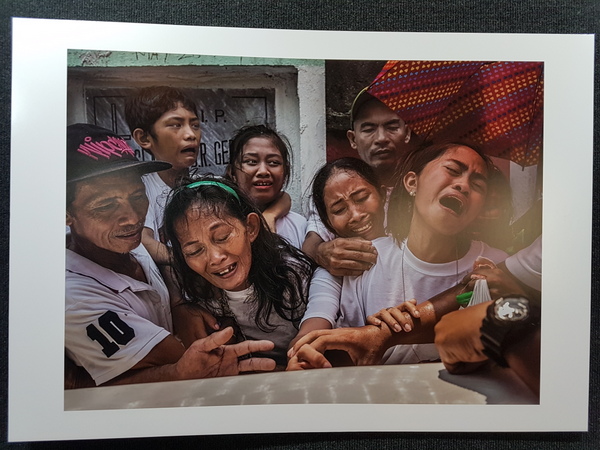

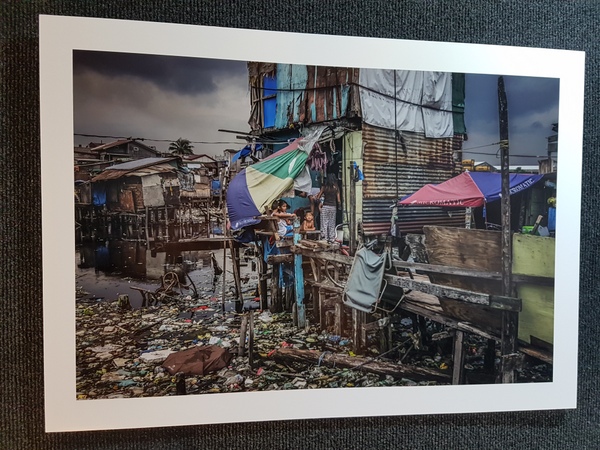

Next up is Normalizing Extrajudicial Murderin the Philippines by American reportage street photographer, James Whitlow Delano.

The images, funded and exhibited by the Pulitzer Center, were taken in Manila following Philippines President Duterte’s ‘war on drugs’ which has led to the execution of over 13,000 people without charge or trial. Most victims live in Manila’s impoverished slum areas, and drug use or petty dealing make them a target for murder. The photos show the brutality of this irrational government policy, and the sorrow and heartbreak cast upon the family of friends of those slain.

While some visitors found Nancy Borowick’s intimate series, The Family Imprint, sad and heartbreaking, others were touched by a story of love and tragedy – it’s interesting how visual interpretations vastly differ!

The photos are of her parents, after they’re both diagnosed with terminal cancer.

‘I photographed my parents to hold on to their memory, and to capture their essence and strength in such a trivial time,’ Nancy writes about the series on her website. ‘Everyone wants to find purpose in his or her life. My parents’ final purpose was found in this moment, in this gift that they gave to me: allowing me to tell their story—a love story—and the story of our family and the legacy they have left behind. When time stops, what was all of this for? They did it for us.’

Photography takes to the streets

Head On features numerous outdoor exhibitions – public displays in parks and gardens, on walls, and shipping containers dotted across Sydney.

There’s around five reportage-style public displays across from the Town Hall at the Paddington Reservoir Gardens, a building that resembles a Roman aqueduct which has been decked out with a lawn and chairs.

These exhibitions are visible from Oxford Street, and lures in a steady stream of visitors.

Beyond photography aficionados, workers on lunch break and passersby will find themselves viewing Craig Holmes’ Of Caravans And Canvas, black-and-white documentary photos of Australia’s oldest circus. Or Dread And Dreams, a series by Afghan photographer, Zalmaï, who returned to document the country in 2008 after fleeing the Soviet invasion in the 1980s.

Beyond photography aficionados, workers on lunch break and passersby will find themselves viewing Craig Holmes’ Of Caravans And Canvas, black-and-white documentary photos of Australia’s oldest circus. Or Dread And Dreams, a series by Afghan photographer, Zalmaï, who returned to document the country in 2008 after fleeing the Soviet invasion in the 1980s.

The eastern chamber of the gardens, an abandoned warehouse-style concrete space covered with graffiti, displays Welcome to Camp America: Inside Guantanamo Bay, a project by wrongful conviction lawyer-turned-photographer, Debi Cornwall.

Debi’s photos are hoisted onto a chain link fence. The prints juxtapose the eerie and empty residential areas inhabited by US prison guards and their families, with tight claustrophobic spaces belonging to prisoners.

The one defining trait that both guards and prisoners share is that neither had chosen to live at Guantanamo bay, Debi says in her description.

While orange jumpsuits and barbed wire is the typical imagery associated with the prison, Debi shows the bowling alleys, a child’s playground and swimming pool, and strange gift shop items such as a ‘I love Guantanamo Bay’ t-shirt. The exhibition also features ‘no faces’ portraits of former prisoners, who were released without charge after years of imprisonment. Debi doesn’t show faces, as the military specified a ‘no faces’ rules when shooting the prison complex.

Opposite Debi’s exhibition is a creative installation of black tarps that vaguely resemble a shanty town structure.

Opposite Debi’s exhibition is a creative installation of black tarps that vaguely resemble a shanty town structure.

Inside is Thom Pierce’s The Price of Gold, a project shots over 20 days in Africa that follows gold miners who are subject to working conditions that can cause an incurable and fatal lung disease.

The other major public space is the Sydney CBD Royal Botanic Gardens.

Walking in from the wrong direction made it difficult to track down the pictures by Head On drawcards, celebrated British photographer Marcus Lyon, and American aerial architecture photographer Jamey Stillings.

Having covered almost the entirety of the park without finding the photos, a staff gardener informed ProCounter there were photos along the outside wall. ‘They’re pretty cool, man!’

And there they were. Quite easy to find, actually – next to the busy footpath that runs along the Cahill Expressway.

A British lady visiting Sydney with her husband was studying Marcus’ Somos Brazil pictures – portraits of influential Brazilian identities. Each print had a map in the bottom corner, which shows where the subject’s ancestors came from based off DNA testing. The project was shot over six months, with subjects nominated, selected, and then photographed.

The photos may make us question our own identity. If the isolated Amazonian tribesman ancestors’ came from a large area across central and south America, then where the bloody hell do we come from?

‘These photos are sort of archetypes of people I imagine you could find in Brazil. I’m not entirely sure, but I think I like the photos, and the artists’ explanation of the project. It’s not “wanky”,’ the lady said. ‘The DNA part of the images is interesting. Oh, and he’s British!’

The lady left. A minute later Marcus walked around the corner, and would have happily explained more about the project.

In fact, all the photographers mentioned in this article – with the exception of Zalmaï and Thom Pierce – were guests at Head On. Many of them spoke at free artists talks, where they spoke about their life and work, and opened the floor to questions.

Festival director, Moshe Rosenzveig, has built Head On with help from a small but dedicated team, a pool of volunteers. Major sponsors from Fujifilm, Olympus, and Sony, as well as industry partnerships with Chromaluxe, WD, Synology, Ilford, Pixel Perfect, Starleaton, and Arthead make Head On possible.

Photography, the medium, may be booming – but the industry has seen better days. Thankfully, those supporting Head On – financially or through volunteering – play a crucial role in creating this spectacular platform that provides opportunities for visual artists.

Moshe’s goal for Head On is to ‘create dialogue between anyone taking meaningful photographs and everyone consuming them’. If the 2018 edition of the festival is anything to go by, then the festival has achieved its goal.

The Head On Photo Festival runs until May 20. Click here for the program.

Be First to Comment