One of the positive trends for 2013 in camera technology is the move to premium-priced cameras equipped with sensors of a larger physical size. And a welcome and long-overdue development it is for specialist camera retailers.

Why? The notion of sensor size (as opposed to megapixel count) is a little complicated to grasp, and gives the specialist salesperson who understands and can convey it to customers a real edge over someone who has just dashed over from the whitegoods or games department in a mass merchants or CE store. It provides a great opportunity for an upsell which benefits both the retailer and the customer.

Less welcome is the absurd push for ever-increasing zoom ranges – but more of that later.

In an era when the smartphone is been identified as a replacement technology for the compact camera, it’s frustrating to see camera makers actually diminish the potential image quality of their products by squeezing ever more millions of pixels onto the same tiny surface area of 6.17×4.55mm – about half the area of an adult’s little finger nail. That’s the physical dimensions of the 1/2.3-inch sensor used in the majority of digital compacts.

(Depth of field control? Why would you want that when you can have everything in focus!)

Most of the 2013 mass market compacts have 16 million tiny pixels crammed on these baby sensors. You could argue that the cheaper digicams are the 110 format of the 21st century; the more things change….

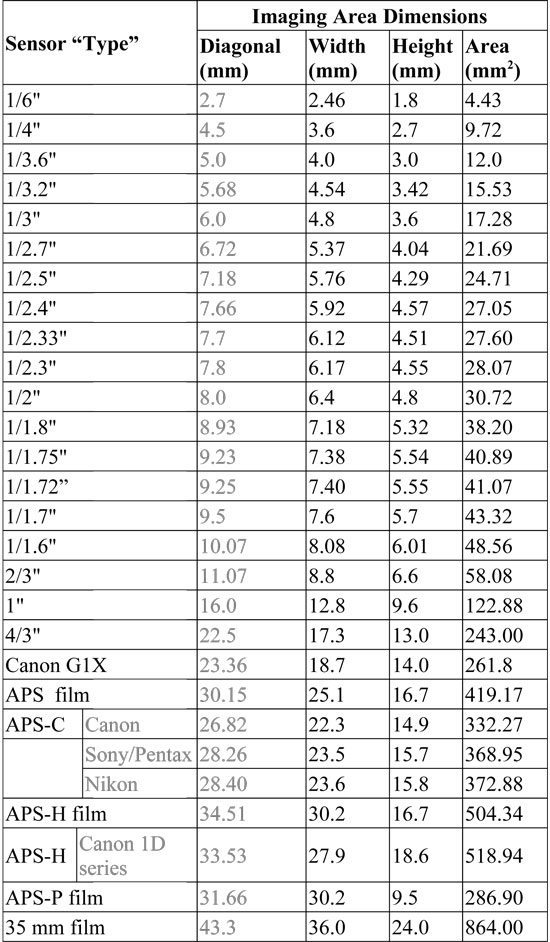

To assist retailers get the ‘size matters’ message across to customers when they are asking you to justify why, say, the 12 megapixel, 5x Canon PowerShot S110 cost almost twice as much ($450) as the not dissimilar-looking 12-megapixel 20x Canon Powershot SX260HS ($250), the chart chart above will help.

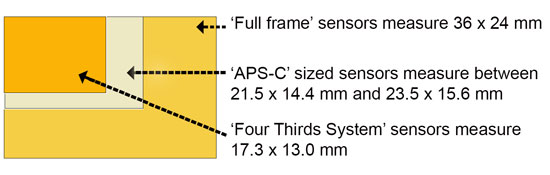

The real kicker is the actual area the different sensor sizes deliver: even though the S110 has only a marginally larger sensor (1/1.7-inch or 7.6×5.7mm) compared to the stock standard 1/2.3-inch or 6.17×4.55mm on the SX260HS, the actual surface area of the sensor gathering capturing light and thus image data is over 50 percent larger – 43 sq mm compared to 28 sq mm. (By comparison, the surface area of an APS-C sensor used in enthusiast DSLRs, some interchangeable lens cameras and premium fixed lens compacts like the Fujifilm X100S is a whopping 330 sq mm or larger, depending on the camera maker.)

There are a lot of other variables, such as the unfortunately-named back-side sensor technology which has boosted pixel and thus low-light performance, and of course, the number of pixels, but whatever the manufacturers’ claims for the performance of their particular ‘intelligent sensor’ technology, sensor size is a fact which can be proven.

Unfortunately, this migration to quality has not been the only, or even the main response from the camera makers to the perceived onslaught of the smartphone. This year will go down as the year the superzoom reared its soft and fuzzy head. Fujifilm leads the carnival here, this week adding another eight superzooms to the five 40x and over models it came out with at CES.

According to 1001Noisy cameras, which keeps a tab on this kind of thing, 42 out of the 82 compact cameras already released this year have zooms ratios of 10x or more.

(That the cameras makers have deluged a shrinking market with ever-more SKUs is another fact to marvel at!)

Now it might be that Fujifilm is going to release the 42x model in, say the US and the 46x model in Europe and the 44x model in Australia and New Zealand, for some arcane global marketing reason. They haven’t said. But I can’t imagine a potential buyer thinking, ‘Hmm, only 44x. I really need a 48x model to truly fulfil my creative objectives…’

Why the world needs even one more 40x+ camera, let alone five of them, is the bigger question…

The difficulty of designing and manufacturing high quality lenses with hyper-extended focal lengths is best evidenced by the fact that in DSLRs, Nikon and Canon and the specialist lens manufacturers such as Tamron and Sigma simply don’t go there. A 28mm – 300mm zoom range (or a little over 10x) is about as far as they’ll stake their reputations. They either can’t do it at a realistic price (keeping in mind that truly top-shelf DSLR lenses attract five-figure prices) or simply can’t do it at an acceptable quality.

So we can safely assume that a 48x lens in a $500 camera will deliver mediocre-to-poor image quality in anything but ideal lighting. And combine these ‘zoom lenses on steroids’ with tiny little 1/2.3-inch sensors, upon the surface of which 16 million pixels have been crammed, it’s very much a case of garbage in, noisy garbage out.

Sales staff need to be mindful of this, especially if the potential customer seems genuinely interested in image quality. If the role is to put the right camera in the right hands, who exactly is the market for a 50x compact? There just aren’t that many photographers out there trying to shoot for the moon.

– Keith Shipton

For an complementary downloadable PDF A4 version of the Sensor Size Table above (courtesy of Margaret Brown), along with crop factor details for key sensor sizes, click here.

Be First to Comment